Read: What do we do about Bach’s St John Passion?, by Robert Harris

Read: Bach as an Interpreter of John, by Gail O’Day

Johann Sebastian Bach

1685–1750

Passio Secundum Johannem

The Passion according to John

Directed by Ivars Taurins

Myriam Leblanc soprano

Krisztina Szabó mezzo-soprano

James Gilchrist Evangelist & tenor soloist

William Sharp Jesus & baritone soloist

Jonathon Adams Petrus, Pilatus & baritone soloist

Projections from The Saint John’s Bible curated by Ivars Taurins & produced by Laura Warren

There will be a 20-minute intermission. The concert will be approximately 2.5 hours in length.

TAFELMUSIK CHAMBER CHOIR

Soprano

Jane Fingler, Roseline Lambert, Carrie Loring, Meghan Moore, Susan Suchard, Sinéad White, Jennifer Wilson

Alto

Kate Helsen, Simon Honeyman, Valeria Kondrashov, Peter Koniers, Karis Tees

Tenor

Paul Jeffrey, Will Johnson, Robert Kinar, Cory Knight*, Sharang Sharma

Bass

Alexander Bowie, Parker Clements, Nicholas Higgs, Keith Lam, Alan Macdonald, Graham Robinson

*Servus recits & solo ensembles

TAFELMUSIK BAROQUE ORCHESTRA

Violin 1

Johanna Novom (leader), Geneviève Gilardeau, Julia Wedman

Violin 2

Christopher Verrette, Valerie Gordon, Cristina Zacharias

Viola

Brandon Chui, Patrick G. Jordan

Violoncello

Keiran Campbell, Michael Unterman

Viola da gamba

Mélisande Corriveau

Double Bass

Dominic Girard

Flute

Grégoire Jeay, Alison Melville

Oboe, Oboe d’amore, Oboe da caccia

John Abberger, Gaia Saetermoe-Howard

Bassoon

Dominic Teresi

Organ

Charlotte Nediger

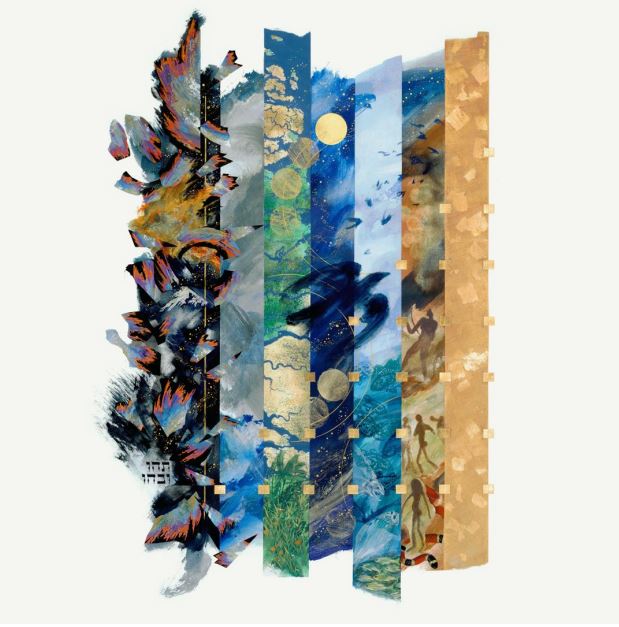

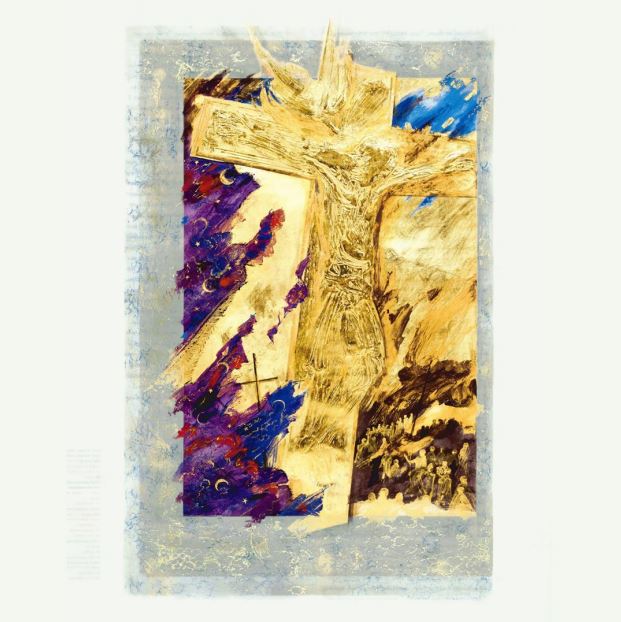

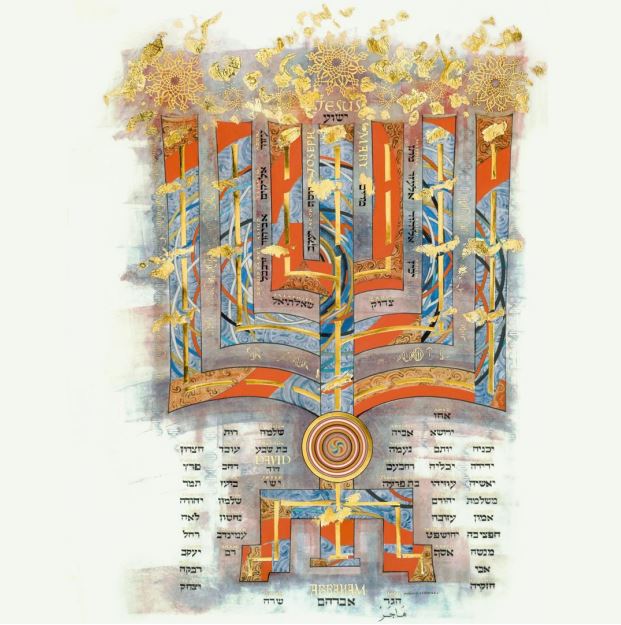

THE ILLUMINATIONS OF The Saint John’s Bible

by Ivars Taurins

| ILLUMINATE: from in + luminare to light up, from lumen-, lumen light. 1a: to supply or brighten with light; 1b: to enlighten spiritually or intellectually; 2a: to make clear; 2b: to bring to the fore; 3: to make illustrious or resplendent; 4: to decorate (something such as a manuscript) with gold or silver or brilliant colours or with often elaborate designs or miniature pictures. (Miriam-Webster Dictionary) |

In the summer of 2019 I stumbled by chance upon a CBC Radio Tapestry program on the creation of the illuminated Saint John’s Bible. I was immediately struck with the idea of somehow bringing this stunningly beautiful work, so vividly described in the radio program, to our performances of Bach’s St John Passion originally planned for March 2020. This led me to contact Katharine Lochnan, the distinguished art historian and curator on the faculty of Regis College (University of Toronto), whose own work on art and spirituality is seminal. (Many will recall her 2016 exhibition “Mystical Landscapes” at the AGO.)

Katharine in turn introduced me to her colleagues at the college, Dr. Gordon Rixon SJ, Dr. Scott Lewis SJ, and Dr. Susan Wood SCL, who told me about the special limited-edition copy of The Saint John’s Bible which resides at Regis. All four scholars have collaborated with me on this project, at the centre of which are the glorious illuminations of The Saint John’s Bible. It was heartbreaking when the original 2020 performances fell victim to the first COVID lockdown. Three years later we are finally able to return to the project, and to share this remarkable work with you.

British calligrapher Donald Jackson had dreamt since childhood of creating a hand-written, illuminated Bible, and found support in a community of Benedictine Monks at Saint John’s Abbey in Minnesota. A committee of artists, medievalists, theologians, biblical scholars, and art historians was established to oversee the creation of the bible. Donald Jackson designed a new script for the text, which was hand-lettered on 1,165 pages of calfskin vellum by a group of six scribes using hand-cut quills and lamp black ink from 19th-century Chinese ink sticks. A team of artists overseen by Jackson used gold leaf and hand-ground pigments and inks to create 160 large-scale illuminations, both ancient and modern in their imagery. From these originals, a limited number of stunning reproductions of the resulting seven-volume bible were produced at the highest quality possible. We are honoured to display two volumes of Regis College’s copy of The Saint John’s Bible in the gym at intermission which you are encouraged to peruse. We are very grateful to have been granted permission to project selected images during our performances of Bach’s St John Passion.

I see the illuminations not only bringing a striking visual element of remarkable artistry to Bach’s masterpiece, but sharing in the universality of the spiritual messages that each work offers. They offer the audience the opportunity, in the words of theologian Henri Nouwen, to truly “step into and walk around” the spirituality of the illuminations while experiencing Bach’s music. With this in mind, I’ve chosen to illuminate Bach’s architecture of the communal experience of the Passion text: the opening and closing choruses, and the chorales.

Thanks are extended to Jim Triggs and Rev. Dr. John F. Ross, former and current Executive Directors, Heritage Program, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University (Collegeville, MN), for granting permission to project the images. Thanks also to those members of the faculty and staff of Regis College, University of Toronto, who generously provided assistance, and in particular to Dr. Gordon Rixon SJ for his support and advice.

Program Notes

by Charlotte Nediger

The tradition of reciting the Passion, or the story of the Crucifixion as recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, was established as early as the fourth century. The texts were read as Gospel lessons during Holy Week, and were to be recited “in a solemn manner.” This manner of recitation, or chant, gradually took on a rough musical and dramatic shape. Manuscripts from the ninth century, for example, include annotations of pitch, tempo, and volume, all indicated by a system of litterae significativae (literally, “significant letters”). The text was divided between an Evangelist, reciting the narrative sections; the role of Christ; and the turba (the crowd), the latter including the various individuals in the Passion and the people as a whole. The Evangelist’s part was marked c (celeriter—moving ahead), and was to be sung at a middle pitch; Christ’s text was marked t (tenere—held back), and was to be sung at a low pitch.

This early framework provided the model for post-Reformation Lutheran Passion settings. The pastor and other clergy intoned the narrative roles of the Evangelist and Christ, the choir sang the increasingly complex turba choruses, and the congregation responded with chorale hymns. Toward the end of the 17th century, the influence of the new baroque form of the sacred oratorio was felt, and the new “oratorio Passion” became popular. Instruments, previously barred from the church during Lent, were introduced. The traditional recitation tones were replaced by composed recitative. Lyrical poems and reflective verses were inserted in the text, and set as solo arias and choruses. Early in the 18th century, Hamburg was the birthplace of the “Passion oratorio”: the emphasis now on “oratorio” rather than “Passion.” Scripture was replaced by completely original texts in large-scale settings that were almost operatic in style and often presented in concert halls or at court, entirely removed from the divine service.

There were many who were offended by such secular presentations of such a quintessentially sacred subject. The Town Council of Leipzig was among them. The influence of traditional Lutheran theology was still strong in Leipzig, and upon accepting the position of Thomaskantor in 1723, Bach had to agree to write works “which would not be of an operatic nature, but would rather excite the listener to greater piety.” For almost two centuries, the Passion had been performed on Good Friday in Leipzig in a simple setting by Johann Walter (c.1530), with the scripture recited in plainchant and simple choral responses. The first Passion of the “modern” type, composed by Telemann, was heard in Leipzig in the Neukirche in 1717. The Town Council reluctantly agreed in 1721 to introduce concerted Passions (i.e. with instruments) in the principal churches of St Thomas and St Nicholas. The traditional morning service on Good Friday was retained, but the Vespers liturgy was adapted to allow for a Passion performance in two parts, one on either side of the sermon. The first was a very modest offering by Bach’s predecessor, Johann Kuhnau.

Bach’s Passion according to John was first performed on Good Friday in 1724, as he approached the end of his first year in Leipzig. Like that of Kuhnau, and as required by his employers, it is an oratorio Passion, the narrative text drawn directly from the scriptures (St John 18–19). To this is added two additional layers of text: free verses set as arias, offering a deeply personal response to the narrative; and old Lutheran chorales, newly harmonized but with melodies and texts that were very familiar to the congregation, offering a collective response. The whole is framed by Bach with two large-scale choruses, introducing a sense of the monumental.

It is unknown whether Bach himself assembled the poetic texts of the non-narrative portions, or whether he worked with a librettist. The choice of chorales, so essential to the overall structure of the work, was probably made by Bach, as was also the incorporation of two passages from the Gospel of St Matthew into the narrative to allow for more affecting representations of Peter’s remorse and of the earthquake that follows Jesus’ death. Throughout, both in the choice of texts and the musical setting, Bach is intent on conveying the specific theology of John’s Gospel and its portrayal of Jesus as “the Word made flesh,” standing outside of the human experience.

Bach revisited the St John Passion on several occasions over a period of 25 years, each time making revisions. For this week’s performances we are presenting the version prepared for the Good Friday service in 1749, a year before Bach’s death. The intensity of the experience of both hearing and performing a Passion is heightened by the baroque practice of the principal singers participating in all aspects: the narrative, the arias, and the choruses. For example, the baritone who sings the part of Jesus also sings the aria reflecting on Jesus’s death. In Bach’s time the four principal singers would have sung throughout, including all of the choral portions. We have moderated this practice to allow voices to manage three consecutive concert performances. Our ripieno group — the choir — is larger than Bach would have known, but this allows the principal singers to sing only a portion of the choral movements. However, the basic premise of inclusion is key to experiencing the Passion as Bach and his contemporaries would have understood it, both on a personal and communal level.

Thank You to our Generous Donors

Tafelmusik is deeply grateful to our generous donors who have continued to support us through this challenging time. Your support has inspired us to remain strong and to deliver joy to our community through our music, and will enable us to persevere until we can once again perform live for you, our cherished patrons. Thank you for believing in Tafelmusik and in the power and beauty of music.

If you would like to make a gift, please click here or contact us at donations@tafelmusik.org.

Thank you to our government sponsors