Photo: Bruce Zinger

Download the Program Notes and Program Listing and Image Credits

Program Notes

by Alison Mackay

The first Toronto performances in early 2016 of Tales of Two Cities: The Leipzig-Damascus Coffee House coincided with the arrival of many newcomers to Canada fleeing from their homeland in Syria. Escaping terrible conflict, they brought with them a rich cultural inheritance which over the centuries had exerted a strong influence on the artistic life of Europe. In a week’s time we will be sharing our exploration of the meeting places of eighteenth-century European and Syrian music, literature, and art with our neighbours to the south in a US tour which concludes in Frank Gehry’s magnificent Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. We are grateful for the opportunity to launch our journey with a remounting of the program in Koerner Hall for our audiences in Toronto.

For centuries, both coffee and music have been celebrated for their stimulating properties and their restorative powers. The development of the coffee house in the cities of the Middle East and Europe offered citizens the opportunity to experience fine music making and coffee drinking at the same time. This was particularly true in the German city of Leipzig and the Syrian capital of Damascus in the eighteenth century.

Though separated by 3,000 kilometres, the two cities had a number of fascinating characteristics in common. Both lay at the crossroads of ancient trade routes and became important centres for international trade fairs.

Leipzig lay at the intersection of the Via Regia (the east-west route from Santiago de Compostela to Kiev and Moscow) and the Via Imperii (the north-south route from Rome and Venice to the Baltic Sea). Merchants from many countries converged on the city three times a year with furs, wines, textiles, and books to be sold at trade fairs which were among the most famous in Europe. Hundreds of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish merchants who were vital to the economy of Leipzig were allowed in the city only at the time of the trade fairs, and they brought their goods from London, Russia, Constantinople, and Spain.

Damascus lay at the intersection of the Via Maris, which linked the Mediterranean Sea with Syria, Iraq, Iran, and the Far East, and the north-south route from Turkey to Yemen and the Arabian Sea. Travellers to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina on the hajj, the pilgrimage required of devout Muslims once in a lifetime, were provisioned for the arduous journey in Damascus, where important trade fairs were established for the sale of silks, jewels, and coffee from the Levant and the Far East.

Both Leipzig and Damascus were also famous centres of scholarship and learning. Leipzig was a vital centre for book publishing and the dissemination of literature and philosophy. Its university, specializing in theology and law, was one of the oldest in Europe and attracted students and scholars from all over Germany.

The ancient city of Damascus, which had been conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1516, was a cosmopolitan hub of intellectual activity. Scholars speaking Arabic, Persian, and Greek used the services of the city’s scribes for their treatises on medicine, astronomy, and philosophy. At the Umayyad Mosque, one of the largest and holiest centres of worship in Islam, there were daily lectures on the Koran and on points of philosophy and law. The Jews and Christians of Damascus were taxed more heavily than Muslims, but they were allowed freedom of residence and of worship in the city’s ancient churches and synagogues, also lively centres of scholarly ferment.

Leipzig and Damascus had another striking feature in common — they both enjoyed a lively tradition of coffee houses in which the finest musicians of the city performed.

The Arabian coffee shrub, or coffea Arabica, was native to the highlands of Ethiopia, but its first recorded cultivation was in Yemen, where members of the Sufi order drank coffee to stay awake during their night-time devotions. Coffee travelled north to Damascus, and by 1540 a Damascene businessman had opened a coffee house in Istanbul. Merchants and diplomats brought coffee drinking to Europe, and by 1700 coffee houses had opened in Venice, Paris, Amsterdam, Vienna, London, and Leipzig.

The year 1701 was a milestone in the history of public performance in Leipzig when the young Georg Phillip Telemann arrived in the city to study law. His fascinating autobiographical writings recount how he took over the direction of a music club called the Collegium Musicum for the students at Leipzig University, many of whom were talented amateur performers. In 1702, the first public streetlights were installed in the city, making it possible for respectable people to be out after dark. Coffee houses soon became a destination for refreshments, conversation, and entertainment, and the student musicians and their performances soon became associated with several local coffee houses.

Telemann’s presence in Leipzig gives us a welcome opportunity to explore the wide range of colours and orchestrations in his vast repertoire of secular instrumental music. A stately French overture begins the programme, which also features music for four unaccompanied violins and a movement from his famous viola concerto (the first known solo concerto for this instrument). Telemann’s lively imagination was sparked by the colourful stories in Gulliver’s Travels and Don Quixote, which were both published in new German translations in Leipzig in the early part of the eighteenth century. His musical depictions of Don Quixote’s exploits are some of the most delightful portrayals of fiction in European music.

Telemann broke his first journey to Leipzig in order to make a special stop in nearby Halle to seek out the acquaintance of Georg Friedrich Händel, who would have been about sixteen years old at the time. The two became lifelong friends and Händel came to visit Telemann in Leipzig. We can imagine that Händel might well have been invited to take part in the weekly Collegium concert, and the works which were later published as a collection of trio sonatas, Opus 2, are typical of the repertoire which would have been performed on such an occasion.

After Telemann moved away from Leipzig, his ensemble became associated with a coffee house in the centre of town run by the confectioner Gottfried Zimmermann, who purchased a number of instruments for the use of the students. In 1729 this ensemble was taken over by the cantor of St. Thomas’s Choir School, Johann Sebastian Bach, who directed weekly concerts for the coffee house patrons, supplementing the ensemble of student performers with members of his family, visiting virtuosi, and Stadtpfeiffers — elite performers from the town band. Under Bach’s leadership the Zimmermann Collegium Musicum became the most highly respected ensemble of its kind in Germany. At this time, the city of Leipzig was already established as a centre for the study of Arabic language and literature. The holdings of the town library included 264 Islamic manuscripts written in Persian, Arabic, and Turkish, which had been acquired in 1686 when Saxon troops plundered the newly conquered Hungarian city of Buda, which had been part of the Islamic Ottoman empire since 1541.

Petition in Arabic to the town councillors of Leipzig written by Georg Jacob Kehr, March 13, 1723. Image used by kind permission of Leipzig University Library.

In May of 1723, the month that Bach moved to Leipzig, a young scholar named Georg Jacob Kehr began to catalogue these manuscripts. He had learned Arabic at an amazing institution in Halle, founded in about 1700 as a social experiment: it was an educational village of fifty buildings “for the use of the entire world.” There was a residence for about 100 orphans, a school for 2,200 girls and boys of all classes, a teachers’ college, a hospital and pharmacy, a cabinet of curiosities, and a “Collegium orientale” — a college offering instruction in Arabic, Ancient Greek, and Hebrew. A famous scholar from Damascus named Sulayman al-Aswad al-Dimashqi, who was involved in the first translation of the New Testament into Arabic and of the Koran into English, taught for a time in this institution, a number of whose graduates became teachers of Arabic in Leipzig in the time of Bach.

A century later, a student in Arabic studies from Leipzig University became the Prussian Consul in Damascus, living there for fourteen years. During this period he acquired for the library of his alma mater a unique and precious collection of 488 manuscripts, most of which were copied in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Damascus. The so-called “Refaiya” collection, named after the family who had the library in their home, contains books of poetry, biographies, letters, travelogues, and scientific treatises, and gives us a valuable glimpse of intellectual life in Damascus in the period explored in our concert.

This collection includes a set of small books that had belonged to a professional coffeehouse storyteller named Ahmad ar-Rabbat. These slim volumes contain stories of the type told in Damascus coffee houses — epic sagas and tales from the Arabian Nights which lend themselves to exciting narration in instalments. The Scottish physician Patrick Russell, who practised for twenty-one years in Syria in the mid-eighteenth century, has left an arresting description of the coffee house storyteller’s art:

He recites walking to and fro in the middle of the coffee room, stopping only now and then when the expression requires some emphatical attitude. When the expectation of the audience is raised to the highest pitch, he breaks off abruptly, and makes his escape from the room.

Our performance includes a story about a destitute migrant who forges a letter of recommendation to a government official. This tale as told by Scheherezade appears in some manuscript collections of Arabian Nights stories, but it originates as a moral tale in a work now known as the Mirror for Princesby the medieval Islamic philosopher Al-Ghazali.The Mirror for Princes was part of the Damascus storyteller Al-Rabbat’s collection; in another manuscript source he explains how to dress the coffee house to set the stage for the storyteller and accompanying musicians.

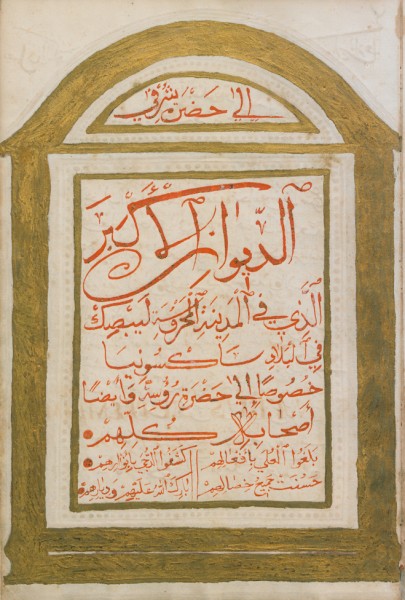

Collection of coffeehouse stories belonging to the eighteenth-century Damascus storyteller Ar-Rabbat.

We are delighted to welcome Trio Arabica, which performs songs and instrumental works from the complex tonal and rhythmic structures of classical Arabic music, and from the styles of traditional music known in Syria which were influenced by Iraqi and Turkish traditions in the cosmopolitan mélange that was a feature of the Ottoman empire.

The Muwashshahis a strophic poetic form using Arabic or Hebrew poems set to music, which flourished in the golden age of Spanish Andalusia. After the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Spain, the form spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa, but was particularly beloved in Damascus and in the Sufi communities of Aleppo.

The dulabis a short instrumental composition based on a set of intervals, or maqam, associated with a certain emotion or mood. A taqsimis an improvised instrumental piece which features a solo player extemporizing within a strict tonal framework. In an Iraqi wedding song from the repertoire of the great Baghdad singer Nazem Al Ghazali, the musicians of Tafelmusik and Trio Arabica find common ground for playing together. We are honoured to be able to share our stage with musicians who inspire us with their skill in improvising, their virtuosity, and their dedication to preserving a beautiful and complex art form from the past.

Many themes which are woven into the Leipzig-Damascus Coffee Houseproject are reflected in the culture of the exquisite Damascene room which has loosely inspired our theatrical set piece. It is a room with exuberant Islamic designs and baroque European influences which was purchased in Damascus in 1899 for the visionary collection of Karl Ernst Osthaus, an important cultural reformer in Germany. After his death the room was donated to the Ethnological Museum in Dresden. Its brilliant jewel-like colours have recently been restored under the supervision of Dr. Anke Scharrahs, who acted as a special advisor to our project.

When a Damascene family was living in this room, it would have been a place for refreshment and relaxation, for the reception of guests, for recitations of poems, for business transactions, and for cross-cultural encounters over coffee. The dividing lines between the ancient communities of Muslims, Jews, and Christians who had been part of the fabric of Damascus for centuries were blurred, and the beautiful calligraphy around the room betrays a desire to make visitors from other traditions feel welcome in the house. The inscriptions render selected verses from a famous poem by Al-Ghazzali (the creator of our story of the forged letter), and they strikingly omit passages in the poem which have overtly religious content so as not to cause discomfort to Christians or Jews, all of whom spoke Arabic in their daily life.

The cultures and economies of eighteenth-century Europe and the Ottoman empire were often marked by violence, intolerance, and slavery. But sometimes ordinary people, including poets, musicians, and artists, sought creative ways to find common ground and to express hospitality to people of other traditions.

In the present time, the people of Leipzig and newcomers from Damascus are seeking similarly creative ways to accommodate and enrich each other’s cultures in their new and challenging reality. In the process of restoring the Damascus Room in Dresden, Anke Scharrahs has trained young Syrian scholars in the restoration of the historical interiors of their homeland. It is her and their dream that they will one day be able to practise their art and enjoy coffee and music in a peaceful Damascus.

Please see a complete list of the images projected during the concert at tafelmusik.org/talesimages.

Follow the orchestra as we take Tales of Two Cities on tour across the US here on our blog.

Young Syrian scholar restoring the wooden panels from Damascus portrayed in our theatrical set. Photo by Anke Scharahs, used by kind permission of the Museum.

THANK YOU

Tafelmusik would like to give heartfelt thanks to the partners and advisors who enriched the Tales of Two Cities: Leipzig-Damascus Coffee Houseproject with their expertise and generous donation of images.

The Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts, Queen’s University (Tricia Baldwin, Director)

The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto (Amirali Alighai, Head of Performing Arts / Dr. Filiz Çakir Phillip (Curator)

The Bach Museum, Leipzig (Kerstin Wiese, Director)

Dr. Anke Scharrahs (Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden, Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden)

Dr. Ulrich Johannes Schneider(Leipzig University Library)

Dr. Boris Liebrenz

Professors James Reilly & Jeannie Miller (University of Toronto)

Dr. Ross Burns• Meredith Chilton(Chief Curator, Gardiner Museum)

Nadia Lotayef Hassan

Mohammad Al Zaibak