A Listening Guide, by Ivars Taurins

Each summer since 2002 at Tafelmusik’s annual Baroque Summer Institute (TBSI), I have coached, rehearsed, and directed a large-scale French mass for the “Grand Finale” concert of the two-week course, most of them by French composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier. Participating singers and instrumentalists join forces with members of the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir and Orchestra, creating an ensemble of over 100 performers. French baroque choral music is often overlooked in a musician’s studies, and a large-scale mass like the Missa Assumpta est Maria, or the Messe à 8 voix, is a great introduction, offering a whole “new” world of music-making and historically informed performance. From solo and small ensemble sections, and instrumental préludes, to the large-scale choral movements, Charpentier’s music challenges and inspires, and is ultimately a rich, rewarding experience, not to mention a perfect finale to TBSI! Over the years my love of Charpentier’s music—its luminescence, rich sensuality, and perfect sense of balance—has never waned.

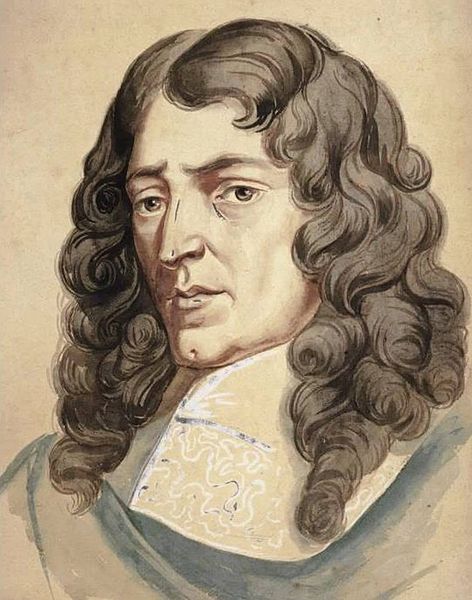

Marc-Antoine Charpentier was one of the most prolific, versatile, and inspiring French composers of the baroque era, a Parisian who lived from 1643 to 1704.

Even if you’ve never heard of Charpentier, there are two pieces that might be familiar. The first is the opening Prélude of his Te Deum, famous as the signature tune for the European Broadcasting Union for the last six decades, and which is played in the opening of Eurovision events, and heard on numerous movie soundtracks.

The second is his Messe de Minuit (Midnight Mass), a Christmas favourite that incorporates French Christmas carols into a mass setting. Have a listen to the familiar opening in this performance led by Christophe Rousset:

But there is much more of this prolific composer that we can explore and enjoy. During his lifetime time he wrote an impressive amount of music, the great majority of his output being sacred music, including psalms, hymns, masses, and oratorios. These were written both for private patrons (in particular, the wealthy duchess, Marie de Lorraine, who employed and housed him for 17 years) as well as the Jesuits, who hired him after the duchess died.

Next to nothing is known about Charpentier’s early life and education—at age 18 he applied to study law, but sometime in the 1660s he travelled to Rome to study music with, among others, Giacomo Carissimi.

Charpentier stayed in Italy for three to five years, and upon his return to France established a successful career, despite the king’s Music Master, Jean-Baptiste Lully, who had a monopoly in all things to do with music at the court of Louis XIV. It could be said that Charpentier brought Italian style with him to France, which is ironic considering that Lully was actually an Italian—Giovanni Battista Lulli—who, seeking his fortune as a young violinist at the court in France, caught the eye of Louis XIV, and became the king’s right-hand man in all things musical, creating a truly French style and becoming more French than the French!

This is music that expresses itself in a very individual way. French composers wrote in a style purposefully distinct from the qualities, or as they saw them, the excesses of Italian style and music. The French proclaimed that their music was more refined, subtle, and eloquent than that of the Italians, which they thought was brash, overblown, overly emotional, and rather crude. Conversely, the Italians considered French music to be dull, insipid, and, frankly, wimpy.

Charpentier’s early exposure to Italian style, and in particular to the music and style of his teacher Carissimi, had a profound and lasting influence on his music, something that drew scathing criticism from some of his compatriots. Many others, though, recognized and admired the exceptional beauty, balance, and craftsmanship of his music.

Let’s listen to an example of Carissimi’s music: the moving, lamenting final chorus “Plorate filii Israel” from his oratorio Jephte.

Now listen to the opening of Charpentier’s chorus “Heu, heu, nos dolentes” from his oratorio Caecilia, virgo et martyr, and one immediately hears something that is more harmonically visceral and immediate—more “Italianate” if you will, even hinting at the madrigal style of Monteverdi, rather than anything in the French “goût” of Lully.

Charpentier composed a number of these histoires sacrées, inspired by Carissimi’s historae sacrae. They were essentially a truncated hybrid of opera and oratorio, with a narrator, solo recitatives, ensembles and choruses, and orchestral interludes. No other French composer explored this genre.

Charpentier’s Messe à quatre choeurs (Mass for Four Choirs) is an early work, believed to date from 1670. It is another example of the Italian influence in Charpentier’s music—inspired here by Italian polychoral works, where multiple groups of singers and instrumentalists would be spatially separated from one another within a church, something no other French composer was doing. The “Et incarnatus est” section shows the luminosity of Charpentier’s harmonic language, as well as the Italianate love of dissonant “crunches” as the individual voice lines criss-cross and collide on the words “et homo factus est” (and was made man): [starts at 15:30 / ends at 17:15]

It was at this time, around 1670, that Charpentier was retained by the influential noblewoman Marie de Lorraine, Duchesse de Guise, known fondly as Mademoiselle de Guise. He enjoyed her patronage for almost 20 years until her death in 1688. An intriguing and influential woman, de Guise chose not to marry, and enjoyed independence from the French court while surrounding herself with art, poetry, and music. Charpentier wrote countless pieces for her, to be performed by her large and highly respected musical establishment of singers and instrumentalists.

In the week before Christmas, the “O” Antiphons for Advent would be heard in the de Guise chapel. These antiphons are a series of seven verses dating from the sixth century. Each antiphon begins with the word “O” followed by a name of Jesus taken from the scripture (they are the basis for the popular Advent hymn O Come, O Come Emmanuel). These eight antiphons were interwoven with popular instrumental carols (noëls).

Intimately set by Charpentier for a small ensemble of voices and instruments, these miniature works express an exquisite delicacy, eloquence, and mystical sensuality that is the trademark of Charpentier’s style. Listen to the sixth antiphon O Oriens: “O Morning Star, splendour of eternal light, and sun of justice: come, come and shine on those who dwell in darkness and in the shadow of death.”

At 1:34 in this excerpt you will have experienced a very special harmony, one that is pretty well unique to Charpentier in 17th-cenury France, and is his harmonic signature. It’s technically called a 9-7 chord. It consists of, if you will, a “tiramisu” layering of thirds: take a triad (do-mi-sol) and then add another third (ti) on top of that, followed by yet another third (re). The result, depending on whether one is in a major or minor modality, is either sensually sweet or sharply dissonant, or anything in between. The “sweeter” variety of the 9-7 chord reminds me of that first mouthful of a fantastic dessert—a tiramisu for me! The more pungent variety of the 9-7 chord reminds me of those lemon candies I had as a child that had a lemony sweet exterior that once dissolved surprised you with a satisfying citric mini explosion!

Listen to this section (“Patrem omnipotentem”) from Charpentier’s Missa Assumpta est Maria (Mass for the Assumption of the Virgin Mary). You’ll experience a whole string of 9-7 chords, used to add a rich expressivity on certain words. At 1:31 and 1:34 you’ll hear two of these chords one after the other as this section comes to a close.

… or in this excerpt from the Gloria of the same mass. It opens with a deep, darkly mystical, incense-filled setting of “and on earth peace, to men of goodwill,” interrupted by a jubilant, soaring section illuminating the words “We praise thee, we bless thee, we worship thee, we glorify thee.” It ends first with a dance-like, flowing setting of “We give thanks to thee…”, and then a majestically extrovert expression of “… for thy great glory.” Charpentier at his best!

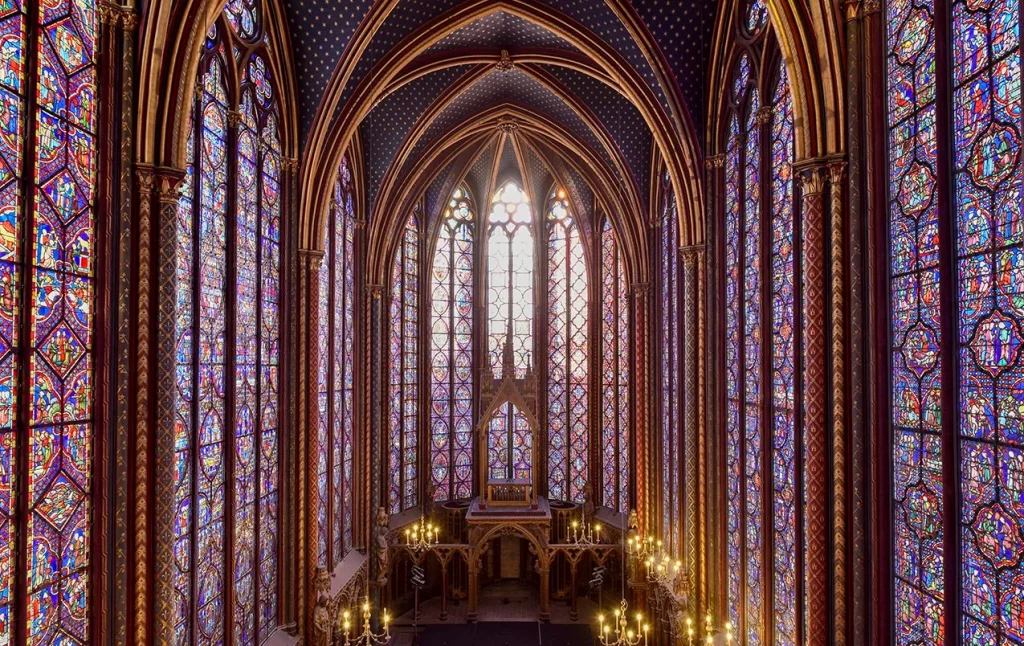

Probably intended for the Feast of the Assumption, this mass was written in 1699, one year into Charpentier’s appointment by Louis XIV as director of music at the magnificent Sainte-Chapelle du Palais in Paris. The Mass is a sumptuous large-scale mature work full of contrasts between small ensembles of soloists, full choir and orchestra, and beautiful sinfonies introducing various sections of the Mass.

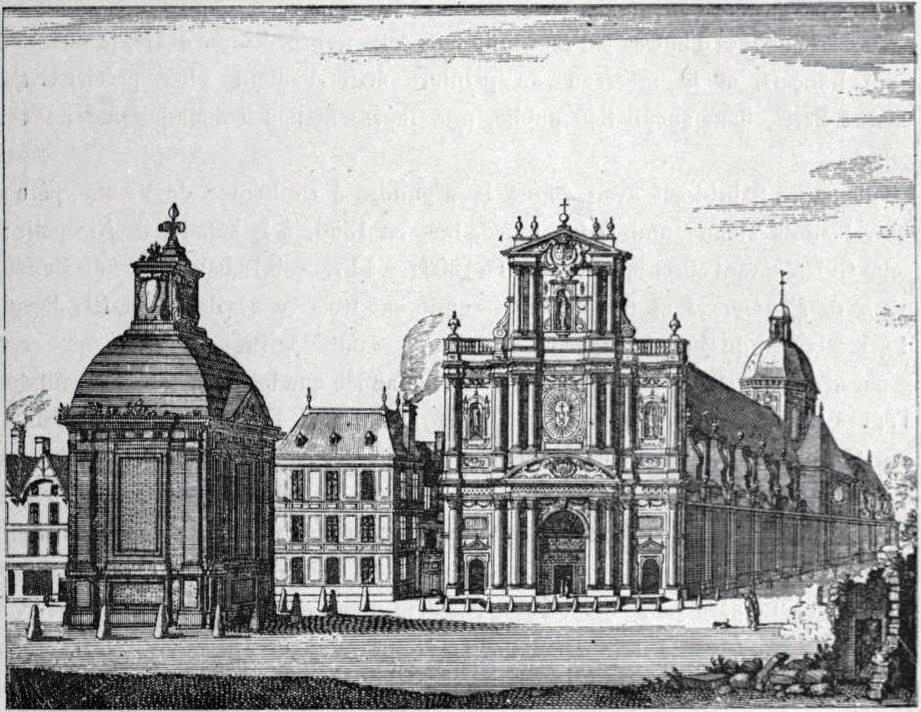

During the 1680s and 1690s Charpentier was maître de musique at the Jesuit Church of St. Louis in the Marais district of Paris. The Jesuits had a liberal approach to the arts and to religious education, and understood the power of oration and rhetoric, as the polymath Marin Mersenne wrote, “to influence, to persuade, perhaps to exhort and instruct.” The role of music in the Jesuit Church was understood to be the conduit through which the listener comes closer to God, and, as in oration, to stir the emotions of the listener.

The services at St. Louis were sumptuous and extravagant, catering to the nobility who attended—the high altar was bedecked in gold and silver, and, like the stagecraft at the Opéra, machines were used to lower the Blessed Sacrament into the hands of the priest, dressed in rich vestments. Fine artwork adorned the altars and walls of the church. The services in this extravagant religious grandeur interestingly included singers from the Opéra, whose names are found written in Charpentier’s scores of the music written for the Jesuits.

During his tenure at St. Louis, he was commissioned to produce a number of compositions for two choirs, including the lavish Messe à 8 voix (Mass for 8 voices). Listen to this section of the Gloria, and the wonderful dialogue created by the two spatially distanced choirs and orchestras, and those wonderfully expressive 9-7 chords on the word “magnam,” Latin for “great” in the sentence “We give thanks to thee for thy great glory.” One can only imagine the effect this music had in the magnificent setting of the Church of St. Louis. [Starts at 10:20 / ends at 13:03]

Although the bulk of Charpentier’s output was sacred music, he also received commissions for secular works. This was particularly true when the Mlle de Guise was his patron. As a wealthy, influential personage, she had sway over the work of artists keen to please her, including the playwright Molière. When he needed incidental music for his comic play Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid) in 1673, the duchess pressured the playwright to hire her favourite composer! Molière had had a falling out with Lully, and his collaborations with Charpentier aroused the jealousy of Lully, who, through the creation of royal patents, forbade the performance of any work without his written permission, and which if ignored, could lead to massive penalties. This gave Lully absolute power over French stage productions, immobilizing any potential rivals. Even under the protective wing of Mlle de Guise, Molière and Charpentier were forced to submit to Lully’s authority, with the result that Le Malade imaginaire had to be revised two times for increasingly smaller forces. A mere six months after this first collaboration, Molière died. Here is a sampling from a production of Le Malade imaginaire mounted in the 1990s, which offers a taste of the French theatre (Playlist #1-3) and shows a different aspect of Charpentier’s creativity.

Track 1: Ouverture (Prologue)

Track 2: Entrée de ballet (Eglogue)

Track 3: Air des reverences (3e intermède)

Eventually, six years after Lully’s death in 1687, Charpentier was able to have his tragedy Médée produced at the Opéra. More sensuous and nuanced in affect, as well as being more diverse in its orchestration than Lully’s operas, Charpentier’s Médée displays a sensitivity to the drama and projection of the characters’ emotions. We’ll end our exploration of Charpentier and his music with a short selection of pieces from the opera, ending with Médée’s breathtaking “Quel prix de mon amour, quel fruit de mes forfaits” (what a price for my love, what fruit of my crimes), sung by Anne Sofie von Otter (Playlist #4-6).

Track 4: Ouverture

Track 5: Noires divinités

Track 6: Quel prix de mon amour