This season, we have been exploring the theme of music as resistance: the ways in which music has given voice to those who have been chronically underrepresented. Our explorations have included a panel discussion which unpacked how music can push back again persecution, oppression, and injustice; and a recent article from Laury Gutiérrez on Antonia Bembo, the remarkable Italian baroque composer who created her own musical language during her self-imposed exile in France.

In this latest article, from Luisa Trisi, learn about the remarkable history of Holocaust music, and the man on a mission to catalog it.

“No one can take music away, no one can imprison it.”

— Francesco Lotoro

By Luisa Trisi

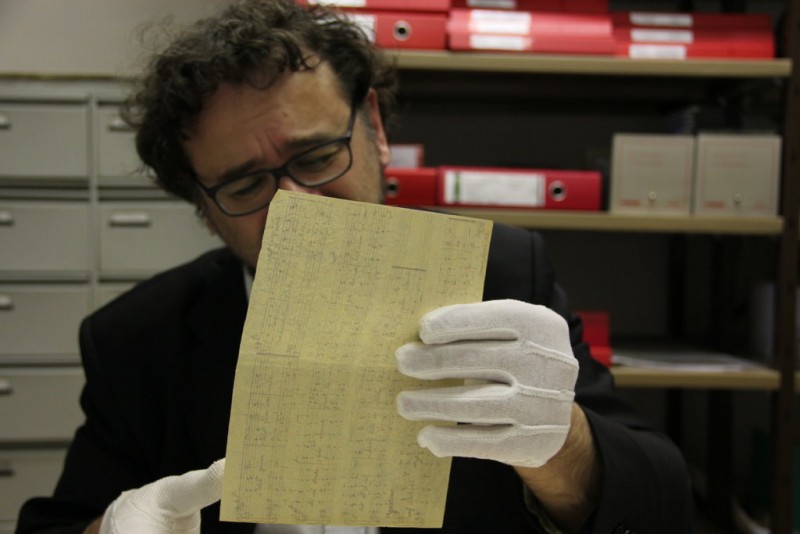

Francesco Lotoro is a man on a mission. For more than 30 years, the Italian pianist and composer has painstakingly researched, collected, performed, and archived music that was secretly composed during World War II amid the horrors of Nazi concentration camps. That music could be created in such inhumane conditions demonstrates the astonishing resilience of the human spirit, and Lotoro’s tireless work to bring it to life is atribute to artistic creativity as an act of resistance.

t the Terezin Museum in 2015, redit: Marc Valenti, via Fondazione ILMC Barletta

Since 1990, Francesco Lotoro has been on a quest to track down death camp survivors and their descendants to uncover music that may have been passed down or committed to memory more than 75 years ago. He has scoured archives and camp barracks looking for hidden musical manuscripts that were scribbled on notebooks, toilet paper, burlap bags, food wrap, or mess tins. “This music was composed in secret and was a way for prisoners to preserve a shred of dignity where none existed,” says Lotoro.

Prisoners Orchestra Sunday concert for SS Auschwitz. Image credit: USHMM (81216), courtesy of Instytut Pamieci Narodowej

Whether composed under the radar or performed as part of official protocol, music was a daily ritual in the death camps. Prisoner bands such as one at Auschwitz-Birkenau consisting of nine violins, two clarinets, two saxophones, cello, trombone, tuba, and double bass, performed Sunday afternoon concerts for SS officers. At the same camp, Gustav Mahler’s niece, violinist Alma Rose, directed the Women’s Orchestra. A teenage cellist in the orchestra, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, survived and maintains that her musical ability ultimately saved her life. Lasker-Wallfisch’s story of resilience resonates even closer to home: her daughter-in-law, the baroque violinist Elizabeth Wallfisch, has been a frequent guest artist at Tafelmusik concerts and tours, and can be heard as the soloist in the orchestra’s 2007 recording of Vivaldi’s L’Estro Armonico.

redit: Jim Watson/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Lasker-Wallfisch is one of several Holocaust survivors who have agreed to share their musical memories with Lotoro, whose home in Barletta, Italy, has become the greatest archive of concentrationary music in the world. Over the past 30 years, Lotoro and his wife Grazia have collected and catalogued more than 8,000 original scores and 12,500 related documents, which will eventually be housed in an ambitious new complex, the Istituto di Letteratura Musicale Concentrazionaria. In addition to conducting research, Lotoro is fundraising to build upon a $5 million contribution from the Italian government towards the future Citadel, a campus that will include a multimedia library, a museum, and a concert hall.

Determined to ensure concentrationary music is heard around the world, Lotoro and his colleagues have recorded and released KZ Musik, a 24-CD set of songs and chamber music composed in death camps. Their monumental undertaking to recover, transcribe, and archive this music is the subject of an award-winning documentary film, The Maestro, and has been featured in reports by The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, CBC, NPR, and CBS.

Lotoro’s archives include symphonies, songs, string quartets, and even a five-act opera, Three Hairs of the Wise Old Man by Czech composer Rudolf Karel, who used medicinal charcoal to write the work on sheets of toilet paper, which were eventually smuggled out of the Pankràc’ prison in Prague.

Despite the apparent contradiction of creativity thriving amid the harrowing setting of the Nazi concentration camps, Lotoro and other Holocaust music scholars agree that the creative impulse was a lifeline for those who hoped that their works would be performed some day, even if they themselves did not survive.

“During the most tragic event in history, humanity set into motion the most civilized mechanisms of self-preservation and managed to spark an explosion of creativity,” says Lotoro. “The composers created music regardless of their surroundings. Deprivation, loss of freedom, and physical discomfort were not obstacles to their creativity; they were, in fact, a powerful incentive.”

Bret Werb, music curator at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, concurs. In an interview with CBS’s 60 Minutes, he said, “music helped people in the camps cope. It helped them to escape. It gave them something to do. It allowed them to comment on the experiences that they were undergoing.”

The work of Polish composer and violinist Jozef Kropinski was almost unknown until Lotoro discovered it in the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and consulted with Kropinski’s son Waldemar in Nuremberg. The most prolific among the concentration camp composers, Kropinski secretly wrote more than 400 works — waltzes, quartets, songs, tangos, and an opera—by candlelight. Waldemar underlined the vital role his father’s compositions played for other prisoners, whose hearts were touched as they listened to music that evoked memories of better times. “Despite his suffering, Kropinski was a man who made himself available to others through music. His efforts created solidarity and camaraderie in the camps,” says Lotoro.

Jozef Kropinski

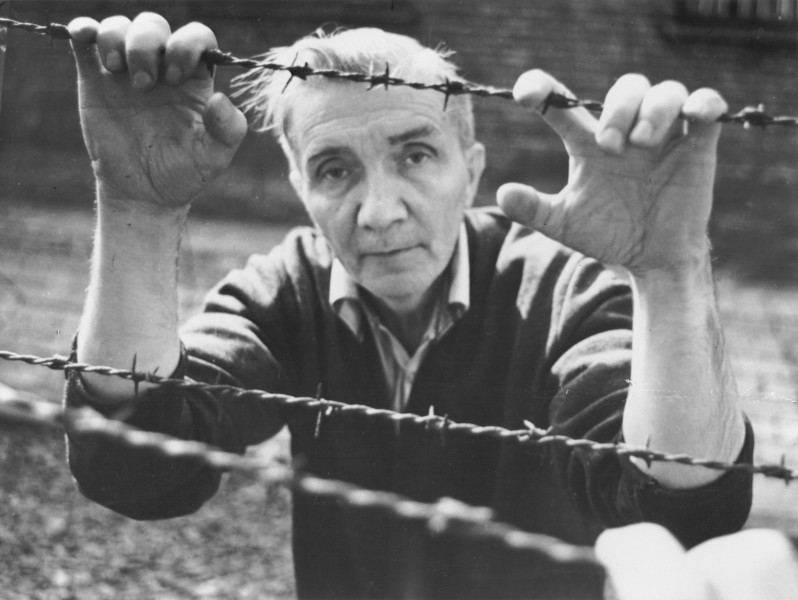

Singer-songwriter Aleksander Kulisiewicz was imprisoned at Sachsenhausen, where he became known as the bard of the barracks. He survived the liberation of the camp in 1945 and spent the rest of his life researching and documenting the importance of music and other creative endeavours for the survival of many prisoners. Speaking to CBS’s 60 Minutes, his son Cristoph recalls that “for my father, music was a way to find a slice of dignity. He used to say, as long as you can sing and compose and you keep it in your head, and the SS officer doesn't know what’s inside your mind, you are free."

Aleksander Kulisiewicz poses holding on to the barbed wire fence at a former concentration camp (possibly Sachsenhausen) during a performance of his collected concentration camp music. Image credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Aleksander Kulisiewicz

Raised Catholic, Lotoro converted to Judaism in 2004 and considers his work to be a mitzvah—a commandment or directive that he is compelled to fulfill. Giving life to scores that were long forgotten and seldom, if ever, performed is his duty. “All of this could have been destroyed, could have been lost. Instead, the miracle is that this music reaches us.”

Though a large part of his efforts are devoted to research and preservation, Lotoro longs for this music to be widely shared. Without regular concert performances and recordings, the music remains trapped and inert, in danger of being forgotten once again. Thanks to Lotoro’s performances, along with those of Yo-Yo Ma, James Conlon, Daniel Hope, Simon Wynberg, and Toronto’s ARC Ensemble, among others, this music is reaching a larger audience than ever before.

“Although it was not possible to save the lives of many musicians who were deported to the camps, we were able to save their music. With every performance, we restore life and dignity to thousands of musicians and their music.”

For more information about Francesco Lotoro’s foundation, the Citadel of Concentrationary Music, visit https://en.fondazioneilmc.it/francesco-lotoro

Francesco Lotoro’s KZ Musik playlist is available here.