by Pippa Macmillan, double bassist

The music of Louise Farrenc may be new to you, but this would be because of her gender rather than the music’s quality. Despite the membership of Tafelmusik having always been a fairly equal mix of genders, probably 99% of all works performed by the orchestra since its conception were composed by men, so it’s high time we shine the spotlight on a long-neglected female composer.

Early life

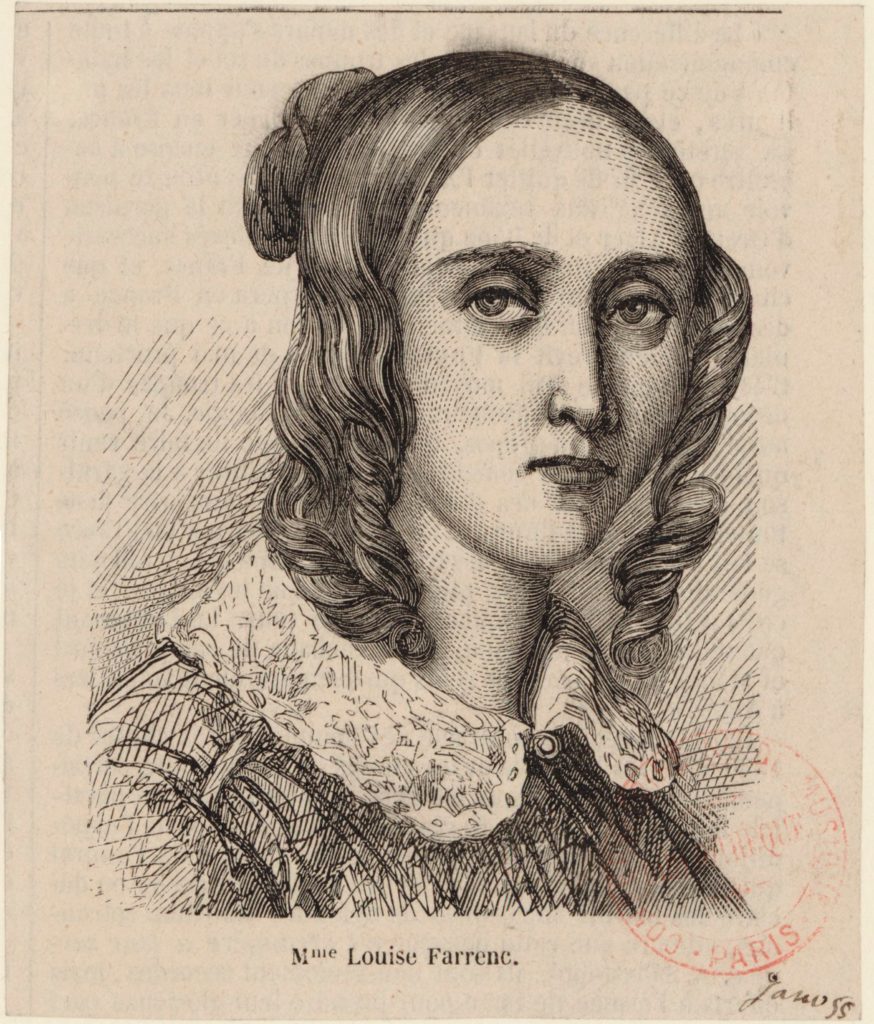

Farrenc was born Jeanne Louise Dumont in Paris in 1804, the year Napoleon was crowned emperor. Generations of her family reaching back to the early 17th century were famous sculptors whose works have been shown at the Louvre and Versailles. Louise was fortunate enough to be born into a bohemian family living at the Sorbonne that encouraged women to explore their artistic abilities.

Farrenc learned piano from the age of six, tutored by a godmother who had studied with Muzio Clementi. She later received lessons from Johann Nepomuk Hummel, among others. With the support of her parents, at the age of 15 she began receiving composition lessons from Anton Reicha. He was a friend of Beethoven, taught at the Paris Conservatoire, and also gave lessons to Liszt, Berlioz, Gounod, and Fauré.

In 1821 Louise married Aristide Farrenc, a flutist who later turned to music publishing. He performed regularly at concerts given at the artists’ colony of the Sorbonne, where Louise’s family lived. Louise’s second good fortune in life was having her husband support and encourage her musical endeavours. After they married the couple travelled together, performing around Europe. Aristide founded what became a leading publishing house in Paris, Éditions Farrenc, and published some of the era’s major composers, including Beethoven. He took his wife’s music everywhere he went as a publisher and helped her get performances. In return, she researched and worked at the compendium they both contributed towards, Le Trésor des Pianistes (The Pianist’s Treasure). This collection preserved the work of earlier composers, and helped revive interest in the music of the past.

Piano music and the Paris Conservatoire

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, Farrenc performed as a pianist, and published her first keyboard compositions through Éditions Farrenc. A number of these were written in the form of theme and variations, such as Air russe varié from 1835 (Playlist #1). This work caught the attention of Robert Schumann, who praised it in his influential Neue Zeitschrift für Musik for its “delightful canonic games” in the spirit of Bach, and declared that “one must fall under their charm.” Unfortunately Schumann’s wife Clara, who also became an accomplished composer and pianist, wasn’t encouraged by her husband in her musical efforts: he wrote in his diary, “having children and a husband who constantly improvises does not fit together with composing.”

In 1842 Farrenc was appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire, and remained the only woman to become a professor there during the entire 19th century. She taught at the Conservatoire for 30 years, becoming a highly respected professor, although she was only permitted to teach women. She and her students performed 17th- and 18th-century repertoire in salons, observing period style which Farrenc, a pioneer of renaissance and baroque music scholarship, researched. Several of Farrenc’s students at the Conservatoire won first prize there, including her daughter Victorine in 1844. However, Farrenc wasn’t permitted to teach composition: not until 1870 were women even allowed to enrol in composition classes. Despite this, Farrenc’s 30 Études in all Major and Minor Keys, op. 26, were added to the Conservatoire’s piano curriculum. The Étude no. 22 from this collection (Playlist #2) trains the left hand to become as dextrous as the right hand with frequent imitation of a quick trill-like figure, and the two hands are often heard to be in competition with each other, or to chase each other up and down the keyboard.

Chamber music and equality of pay

Farrenc moved next to chamber music, writing piano quintets, piano trios, and violin and cello sonatas in the 1840s. She became best known for her chamber music, especially two piano quintets that were popular among critics. Luckily for us, the Australian historically inspired chamber ensemble Ironwood has recorded the Quintet for piano and strings no. 1 in A Minor, op. 30 on period instruments, including an original Érard concert grand piano from 1869. Enjoy the luscious sound world of the second movement, an Adagio non troppo (Playlist #3).

Farrenc won the Chartier Prize for chamber music from the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1861 and in 1869. It cited her for works that “glow with the purest classical style.” Felix Mendelssohn also drew praise for working within the confines of older traditions. His older sister Fanny Mendelssohn, born a year after Farrenc, received the same musical education as Felix, and composed prolifically. However she was discouraged by her father and brother from publishing her music, and didn’t enjoy the same recognition as Farrenc during her lifetime.

Paid far less than male professors at the conservatoire, Farrenc often protested to the authorities, and tried to gain equality for nearly a decade. After the successful premiere of her Op. 38 Nonet for strings and winds (Playlist #4, third movement: Scherzo. Vivace) she asked again, and finally she was granted equal pay to her male colleagues in 1850. The premiere of the Nonet featured the virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim, and the writing highlights the qualities of each instrument.

Orchestral music

Farrenc’s orchestral works date from 1834–47: two overtures and three symphonies. All were performed multiple times in Paris during her lifetime and some were heard abroad. However, unlike her piano and chamber music, none of her orchestral music was ever published, and it was quickly forgotten.

The influence of Beethoven is clearly evident in the third movement of Farrenc’s Symphony no. 1: Minuetto. Moderato (Playlist #5). The music looks back to the classical style of Mozart and Haydn, but with a turbulent and dramatic edge. Like Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5 it’s in the key of C minor.

Farrenc’s Symphony no. 3 premiered in 1849, at a concert at the Société des concerts du Conservatoire de Paris in which Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5 was also performed. Indeed, between 1831 and 1849 Beethoven’s music closed the concert every time that a symphony was performed there by a living composer. However, the symphonic genre was out of fashion in Paris at this time: French audiences were more interested in opera and chamber music. Opera is missing from Farrenc’s oeuvre, but it could be that she didn’t succeed in receiving a libretto to set to music.

Here is the Finale of her Symphony no. 3 (Playlist #6). Critics (many of whom expressed surprise that a woman could compose powerful music) wrote about the piece often, even several years after its premiere: “There is no musician who does not remember Mme Farrenc’s Symphony performed at the Conservatory, a strong and spirited work in which the brilliance of the melodies contends with the variety of the harmony.”

Later years

After the early death of her daughter in 1859, Farrenc retreated from composition, writing only a few miniatures. She arranged a series of lecture-recitals in 1862, at which her students paired works of hers with those by Byrd, Frescobaldi, Rameau, and others. By the time of Aristide’s death in 1865, there were eight completed volumes of their edited compendium of piano music spanning three centuries, Le Trésor des Pianistes. Louise added a further 15 volumes. By the time of her death in 1875 she had succeeded in being a performer, composer, professor, publisher, and equality campaigner.