This summer, we are saying a heartfelt goodbye to our Tafelmusik Media consultant, Randy Barnard, who—after a storied and decades-long career in the industry—is stepping away to embark on new adventures.

Before we share our conversation with Randy, he asked that we share this sentiment:

“With the recent and untimely passing of Jeanne Lamon, it’s emotionally difficult to reflect on my time with Tafelmusik. It’s impossible to talk about the orchestra without referencing what an extraordinary artistic leader, musician and person Jeanne was and how she shaped and refined the unique, and internationally acclaimed baroque ‘sound’ of Tafelmusik. I consider myself to have been very fortunate and blessed by my professional and personal association.”

Below, enjoy our insightful conversation with Randy Barnard about his career, his insights, and his time with Tafelmusik.

Randy Barnard, sporting his Tafelmusik shirt

How did you get your start in the music industry? What was your first early role?

Randy Barnard: It depends on how far back you want to go, as my first professional music gig was in high school—as part of a rock and roll cover band!

TM: Fun! Tell us more about that.

RB: We were called Paxton’s Back Street Carnival, named after a song from Strawberry Alarm Clock’s album “Incense and Peppermints”—we picked up on that one track as our as our band name. And it stuck.

We were all having fun in high school. I played a couple years after I graduated high school: we played Ontario, we played Winnipeg a lot, Thunder Bay, North Dakota, exciting places to tour.

They say your formative years are between 16 and 22—the music you engage with then kind of sits in your brain forever. It sits in my brain now, for sure. We covered Credence Clearwater Revival, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, all those bands. We had a purple touring bus, which we renovated: it was a huge yellow school bus, which we painted purple, of course, and it housed or bunk beds and equipment. It was a lot of fun.

What came next, in terms of your early music career?

RB: The cover band lasted about five years, which led me to Ottawa's Carleton University to study composition, where I graduated with a Bachelor of Music.

While at university, my summer employment was as an audio engineer with CBC Television. After graduating, I was hired into CBC Radio as an associate producer, with a brand new program called “Arts National”: it was a combination of music journalism and concert presentations from across the country.

My first real early role which offered the opportunity to formulate production and artistic direction expertise was in Winnipeg, where as a producer, I was responsible for creating a series of studio and concert programs with the former CBC Winnipeg Orchestra.

CBC at that time had two house orchestras based in Winnipeg and Vancouver. Neither exist any more, but at this time in my career, I developed radio orchestral programs that offered a fabulous exposure to national and international radio audiences for Canadian conductors, composers, and soloists. The work with the CBC Winnipeg Orchestra was complemented by broadcasts with the Winnipeg Symphony and the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra.

Winnipeg was and is never lacking in a fantastic classical talent base, and it allowed me the opportunity to record broadcast of soloists, choirs, composers, and smaller chamber ensembles. I produced hundreds of broadcasts for regional and national broadcast, and independently produced some 30 commercial recordings.

Were you explicitly drawn to classical music as a genre? How did you get into classical music specifically?

RB: Well, the interesting thing about working in the CBC’s regional centres across the country is that I had a broader role: it was part of the CBC’s fascinating substructure of time, whereby throughout the country, they had a series of producers who worked in these various regional centres. It was a structure that allowed us to discover talent and expose younger artists on a regional level. If they were talented enough, they also graduated to exposure on a national level. And, we had the benefit of guiding that process.

As a producer, I was afforded the opportunity to work with not only orchestras, but also soloists and choirs. I could create large and small ensembles, I wasn’t restricted to a certain core. I was very lucky. And Winnipeg was and remains a great cultural centre in many ways. And we were never ever lacking for great music and great musicians.

It was these experiences that solidified my work in, and my draw to, classical music.

How did you first come to know, and work with, Tafelmusik?

RB: If you listened to CBC Radio Music programs in earlier times, Tafelmusik was featured many times. Their concert broadcasts could be heard as many as a dozen times over the year.

As a CBC listener, they became familiar—but as a CBC producer, I marvelled at the wonderfully high quality of the artistic and performance base. For their unique focus on the baroque repertoire, they were second to none. Their concert broadcasts were complemented by several CBC disc programs which featured commercial recordings, primarily with the Sony label.

The first opportunity I had to work with the orchestra directly came when I moved to Toronto as a senior manager in CBC Radio Music. As with other major orchestras across the country, the CBC—at that time—recorded and broadcast concert performances on a regular basis. Being in Toronto, however, offered me the opportunity to attend Tafelmusik concerts in person, and more importantly to meet on a regular basis with the artistic and administrative staff to develop concert broadcasts for CBC Radio and commercial recording projects for CBC Records.

You worked as head of CBC Records. Can you talk about your experiences there, and the artists you recorded with them? What has CBC Records’ existence has meant for Canadian classical artists and their international profiles?

RB: Yes: my last ten years of some 35 years with “mother corp” was as General Manager for CBC Records. CBC Records was a formidable classical label in Canada, one of the few at the time that featured Canadian composers, soloists, choirs, and orchestras. There were also numerous historical recordings released that were drawn from the archives, including Glenn Gould, Maureen Forrester, and the Canadian Brass.

When I first took over as General Manager, the label concentrated mainly on traditional orchestral repertoire that would be broadcast on disc programs. I began to include more recordings that featured soloists, and what a fantastic group I could draw on! Among others, the first commercial recordings of James Ehnes, Angela Hewitt, Gerald Finley, Michael Schade, Russel Braun, Karina Gauvin, Isabel Bayrakdarian, and Measha Bruggergosman were on CBC Records. I also developed full albums featuring Canadian composers, and as CBC Radio Music programs expanded into other music genres, the label released jazz, blues, world and traditional recordings.

When I left CBC Records, the catalogue boasted some 400 recordings, 30 JUNO awards, and a Grammy. I was General Manager for 21 of those national and international awards. I worked with every major orchestra across the country, and as mentioned, with many of Canada's best composers, instrumentalists, vocalists, choirs and ensembles. I also signed new national and international distribution deals which brought the profile of these incredible artists to a far larger consumer and audience base.

You touched on this above, but: you’ve worked with some of Canada’s biggest names over the past 3+ decades, and you’ve been a member of the JUNO Classical Advisory Committee for many years. Can you speak a bit about some of the bigger names you’ve worked with? Most exciting experiences you’ve been a part of?

RB: That's a hard list to narrow down, but I will single out one artist that I feel CBC recognized an extraordinary talent from the very beginning, and that's violinist James Ehnes. I mentioned that CBC Records released James' first recordings, and they enjoyed immediate praise and sold extremely well in the commercial market. His Mozart violin concerto recordings, the Bruch concertos with the Montreal Symphony and the Korngold, Walton and Barber Concertos with the Vancouver Symphony are extraordinary. They all won JUNOs, and the Vancouver recording garnered a Grammy. It doesn't get much better than that!

I do want to point out two orchestras as well in the “biggest names” category, and that's the Montreal Symphony and Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra. Their respective discography and international profile was incredible—much to do with their then exclusive commercial recording contracts. This exclusivity eventually ended, and it offered CBC Records the opportunity to re-engage with commercial recording projects. This too stands out as amongst my most exciting experiences.

You were integral to launching Tafelmusik Media—our in-house record label—in 2012. Can you speak about how the label has grown over the past nine years, and how it has adapted to constant changes in the industry?

RB: When an orchestra is signed to a project with a record label, the orchestra does not have complete control over what repertoire or soloists are featured—and more importantly, in most cases, does not own full rights to the master recordings.

In 2012, spearheaded by then Managing Director, Tricia Baldwin, and after much research into the pros and cons of creating Tafemusik's own label, Tafelmusik Media was launched, primarily to be in complete control of the artistic direction, the recording process, and the release schedules. The label developed a plan to release a balance of original unique audio and video recordings, with licensed projects from former label associations including Sony, Analekta and CBC Records. Over the past nine years Tafelmusik Media has released 23 recordings, including 5 video productions. For an independent label, that's an incredible feat! Speaking personally, the administrative commitment and dedication to these tasks at Tafelmusik are rare and to be commended.

To complicate matters, Tafelmusik Media is competing in what can only be called a “vicious” market, whereby there are hundreds of classical recordings released on an annual basis—and, figuring out what and how the consumer listens and buys classical music is mind numbing.

Physical products (namely CDs and DVDs) remain important to the classical buyer, and this is especially true of off-stage sales at concert performances. With the current pandemic restrictions, however, physical sales at concerts are non-existent. Physical sales of classical music nationally and internationally are also suffering, and that is due to the very sophisticated current delivery of digital content through digital downloads and streaming. The digital platforms offer the consumer an incredible choice of content—and superior audio if wanted—at reasonable prices.

Tafelmusik Media is small, but it's mighty in this fight.

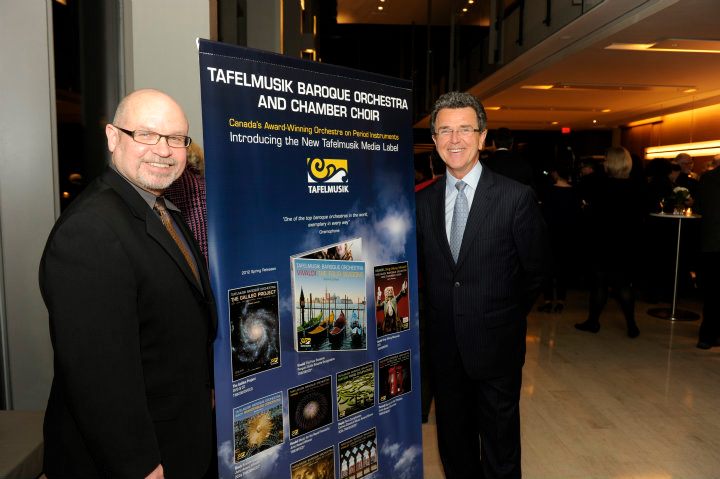

At Tafelmusik Media's launch party: Rick Dunlop of Naxos Canada at left, Randy Barnard at right

You spoke about the shift from CDs and physical products being the norm, to digital streaming taking over. Can you talk a little about this trajectory, and how it has affected classical music? Your own listening habits?

RB: Hey… what about vinyl! What about cassettes? I've been around for awhile, and vinyl is actually making a comeback!

That said, digital streaming is definitely the powerhouse for the consumer, and as mentioned above, for very good reasons in terms of delivery of superior content to the demands of the consumer at a reasonable price.

I'm a convert to streaming, not only for my personal listening across many genres, but as a professional tool. As a music consultant, I need to be aware of what's new and trending. You mentioned my involvement with the Classical JUNO Advisory Committee, where on our annual review, we entertain on average some 100 recordings over four categories. What better provider than Spotify to assist in that review?

Personally, when it comes to classical music, I have my favourite recordings stacked up in my CD (and vinyl) library—but I seldom play them: I’d rather take a far easier route, and “ask Alexa” to play it for me. Quality is an issue, but the convenience wins out almost every time.

When my friends talk about recordings they favour, or which are new to them, a quick check in on Spotify sparks the conversation.

Can you tell us a little about the specific challenges or intricacies of working in classical music, from the distribution side? What differentiates it from, say, pop or rock music?

RB: The classical music share of the market is around 2%, which falls well behind the top four genres: R&B and hip-hop; rock; pop; and country. And then there are genres like children's music, Latin, electronic, Christian and gospel, world, jazz, blues, and seasonal markets to name a few. Competition? What competition?

However, although the classical market is thought of as attracting older audiences (over 55), recent research shows significant increases in listeners under 35. This is probably due to the digital content platforms offering up playlists that cross many genres, but are driven by one’s mood or personal choices at any given time. Classical music fits extremely well in these playlists.

In the context of running a record label, it's as important to consider building playlists from your discography as it is to release the more traditional album of unique original repertoire. Tafelmusik has pursued this and has launched thematic albums—Baroque for the Brain, intended for students and studying; and Baroque for Baby, intended for babies and toddlers—in this context.

What about the technical differences of recording classical music? From an audio engineering perspective?

RB: You approach classical recording in a far different way than you normally would with a pop or jazz recording. It’s different from laying down individual tracks in an isolated environment for each of those particular instruments and/or vocals. You put it on a multitrack situation and you spend a lot of time in post-production mixing those tracks down for your ultimate result.

The thing about classical music is that you actually record the room. The hall itself becomes as much as an instrument as the ensemble. This is why the renovations that were done to Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul's Centre (Tafelmusik’s home venue) were so important, because they actually provided a fabulous recording environment, and they provide a fabulous listening environment for the for the audience, of course.

The acoustic treatment of the of the hall and the various things that you can do in terms of making it a beautiful space to listen in are important: the classical producer and classical engineer try to capture the sound in its entirety within that room.

The microphone setup is just as complicated as a pop recording, but instead of focusing on individual instruments or voices, you’re looking to capture the whole sound at once. We still multitrack, but the general sense is that you capture the whole room as best you can.

Tafelmusik is a relatively small ensemble. The size of the band expands of course, depending on what’s being played—but it's never in the 80 to 100 capacity, like some larger modern orchestras. It's a little bit more complicated when you bring in choirs and soloists, but not extraordinarily so because again, they're playing in the environment of their hall. And that's what you're trying to capture: that magical sound that comes out of the choir, but resonates in the hall.

Are there any contemporary classical or baroque artists (besides Tafelmusik!) that you are currently drawn to, or listening to on repeat? Who should we be tuning in to?

RB: I tend to favour the more traditional ensembles: the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Academy of Ancient Music, and the Baltimore Consort. Red Priest pushes the envelope.

Canada boasts some great ensembles, although not on period instruments: Les Violons du Roy, I Musici de Montreal, the Pacific Baroque Orchestra, La Pietà. Tafelmusik's own orchestra members also create some of their own ensembles, and let's not forget Opera Atelier. What a feast!

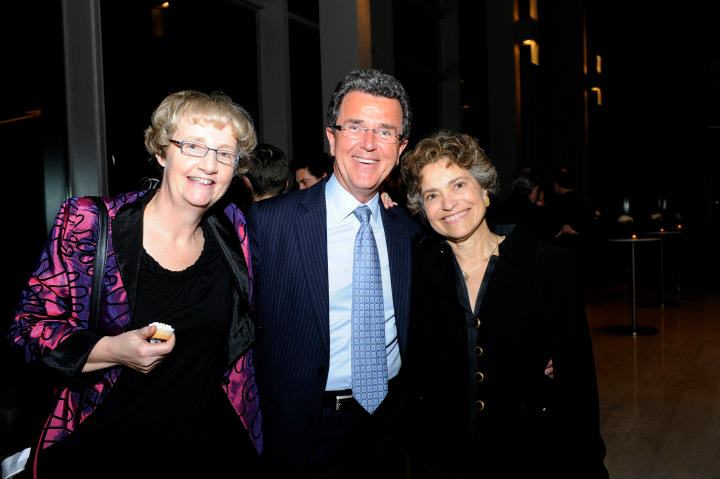

Randy Barnard posing with former Managing Director Tricia Baldwin, left; and Music Director Emerita Jeanne Lamon, right

Can you share how you plan to spend your time pursuing other activities in this next phase of your life?

RB: It’s not really a retirement in my mind, rather, a different kind of mix that allows more time with family and more time to travel. Pandemic restrictions aside, my wife Linda and I are at an age and position in our lives that allow this pleasure, and it's one we hope to begin sooner than later.

Professionally, I am not taking on any more long-term clients but I’m considering short term or one-off projects.

And I will especially reflect on the fantastic and looooooong lasting relationship I have had with Tafelmusik, for both personal and professional reasons. They are my friends as much as my colleagues.

The artistic and administrative leadership has been extraordinary; the administrative staff and the board are exemplary; the orchestra and choir are second to none. I will miss the commitment, humour, dedication, debate—and finally, after so many wonderful years, it will be difficult indeed to take a back seat to their recording endeavours. But, like everyone else, we wait with anticipation for the downbeat at their next live public concert, and in the meantime, continue to listen to and watch online and on disc, the incredible legacy of recorded music at the hands of the Taflemusik Baroque Orchestra and Chamber Choir.