Aisslinn Nosky, guest director

Live performances:

October 28, 2022 at 8pm at Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s United Church

October 29, 2022 at 2pm at Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s United Church

Program

| Anton Reicha 1770–1836 | Wind quintet in E Minor, op. 88, no. 1 (Paris, c.1818) Introduction Marcello Gatti, flute Marco Cera, oboe Tindaro Capuano, clarinet Dominic Teresi, bassoon Pierre-Antoine Tremblay, horn |

| Felix Mendelssohn 1809–1847 | Octet in E-flat Major, op. 20 (Berlin, 1825) Allegro moderato ma con fuoco – Andante – Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo – Presto Aisslinn Nosky, Cristina Zacharias, Patricia Ahern & Geneviève Gilardeau, violins Patrick G. Jordan & Brandon Chui, violas Keiran Campbell & Cullen O’Neil, violoncellos |

Intermission

| Louise Farrenc 1804–1875 | Nonet in E-flat Major, op. 38 (Paris, 1849) Adagio/Allegro – Andante con moto – Scherzo: Vivace – Adagio/Allegro Marcello Gatti, flute Marco Cera, oboe Tindaro Capuano, clarinet Dominic Teresi, bassoon Pierre-Antoine Tremblay, horn Aisslinn Nosky, violin Brandon Chui, viola Keiran Campbell, violoncello Dominic Girard, double bass |

The musicians in Trailblazers are playing instruments appropriate to the first half of the 19th century. It is the first time Toronto audiences are hearing wind instruments from this period. Read Marco Cera’s blog recounting his and Dominic Teresi’s adventures in procuring new instruments for the occasion.

Program Notes

by Charlotte Nediger

Reicha Quintet

The Czech violinist, flutist, and composer Anton Reicha was born in Prague in 1770. Following the early death of his father, a town piper, he was adopted by his aunt and uncle, Lucie Certelet and Josef Reicha, the latter a virtuoso cellist, composer, and conductor. The family settled in Bonn when Anton was 15, where he played flute in his uncle’s orchestra alongside Beethoven, his exact contemporary. The two became friends, both studying composition with Christian Gottlob Neefe. Josef apparently discouraged his nephew’s composition studies, but by age 25 Anton had vowed to abandon performance, devoting himself to composition, teaching, and reading philosophy and mathematics alongside music theory, leading to interesting experiments in counterpoint and writings on music.

After stints in Hamburg and Paris, and some years in Vienna with Beethoven and Haydn, Reicha settled in the French capital, where he was appointed professor of counterpoint and fugue at the Paris Conservatoire, writing three influential textbooks on composition. Among those who studied with Reicha are Berlioz, Liszt, Gounod, Franck, and Onslow—and appropriately for this program, both Felix Mendelssohn (albeit briefly) and Louise Farrenc.

Among Reicha’s most popular works were his wind quintets for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn. Honoré de Balzac’s novel Les Employés ou la Femme supérieure includes a fictional character who plays clarinet at the Opéra-Comique: he convinces a friend to join him at a soirée by promising him the great excitement of a new wind quintet by Reicha.

Mendelssohn Octet

Felix Mendelssohn displayed musical gifts from a remarkably early age. He was arguably as prodigious a pianist and composer as Mozart before him, but his parents chose a different childhood for their son. Rather than parading his talents around the courts and concert halls of Europe, they kept him at home and concentrated on a comprehensive education. The Mendelssohn household was a remarkable one: Felix’s paternal grandfather was the great philosopher of the Enlightenment, Moses Mendelssohn, and the family house in Berlin was host to many of Germany’s leading thinkers and artists. Felix’s well-to-do parents provided a strong intellectual, cultural, and artistic education, and the young Felix exhibited talent not just for music, but also for poetry and visual art. At the age of ten, Felix’s musical education was expanded to include the study of composition and theory with Carl Friedrich Zelter, principal of the Berlin Singakademie, at the suggestion of his maternal great-aunt Sarah Levy. Levy was a celebrated harpsichordist, a student of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and friend of his brother Carl Philipp. Her choice of Zelter was to prove significant in forming Mendelssohn’s style as a composer. Zelter insisted on careful and thorough study of the works of baroque and classical composers, music that appealed to Mendelssohn and to which he would continue to turn throughout his life. By age 12, Mendelssohn’s homework included the composition of symphonies and concertos, performed at concerts at the Mendelssohn home by a private orchestra, led from the keyboard by Felix, with the intellectual elite of Berlin in attendance.

By 1825, the year of composition of the Octet for strings, the 16-year-old Mendelssohn had composed some 150 pieces. Robert Schumann noted in his memoirs that Mendelsohn’s “favourite piece from his early years was the Octet; he recalled with delight the wonderful period in which it was written.” Early in the year he had spent time in Paris, meeting musicians, artists, and thinkers who sparked his imagination. Shortly after his return, the Mendelssohn family moved to Berlin’s Leipziger Strasse, offering new possibilities. From this arose the very singular Octet op. 20. The autograph score is preserved in the Library of Congress (you can view it here). It was presented by Felix as a birthday gift to his friend and violin teacher, 23-year-old Eduard Ritz. The norm in string octet writing was to have two string quartets playing in dialogue. Although scored for the same cohort of strings, Mendelssohn’s octet has them play as one entity. Mendelssohn later added a note to the parts that the Octet “must be played in all parts in the style of a symphony; the Pianos and Fortes must be executed with great precision, and shaped more distinctly and individually than is otherwise customary in pieces of this genre.”

Mendelssohn revisited the Octet in 1831, taking it with him on an extended trip to Paris, and approaching music publishers in Leipzig with a substantially revised version, as well as an arrangement for piano four-hands, both published in 1833 as opus 20, and dedicated to his friend Eduard Ritz, who had died while Mendelssohn was in Paris.

The Octet includes a particularly delightful Scherzo. Felix’s sister Fanny recounted that her brother had wanted to set to music a stanza in Goethe’s Faust:

Wolkenzug und Nebelflor

Erhellen sich von oben.

Luft im Laub und Wind im Rohr,

Und Alles ist zerstoben.

Flight of clouds and veil of mist

are lighted from above.

A breeze in the leaves, a wind in the reeds,

and all is blown away.

Fanny continues, “To me alone he told this idea: the entire piece is to be played staccato and pianissimo, with shivering tremulandos and the gentle lightning flashes of trills. Everything is new and strange, yet so appealing and familiar—one feels so close to the world of spirits, swept up into the air. Indeed, one feels half inclined to snatch up a broomstick so as to follow the airy legion. At the end, the first violin soars upward, as light as a feather—and all is blown away.”

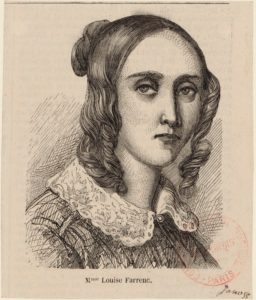

Farrenc Nonet

Louise Farrenc, née Dumont, was born in Paris in 1804 into a family of renowned painters and sculptors. Her musical talent and skills as a pianist were evident from an early age, and when she enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire at age 15 she took up composition studies with Anton Reicha. She interrupted her studies briefly to marry flutist Aristide Farrenc and to undertake a concert tour with him. Aristide became disillusioned with performing, opting instead to found a music publishing firm, giving Louise an outlet for her early piano works. Her 30 Études in all the major and minor keys were adopted as required study for all pianists at the Conservatoire. Renowned for the excellence of her teaching, Louise was appointed professor of piano at the Conservatoire in 1842, the only woman in the 19th century to hold a permanent post of this significance.

Louise Farrenc went on to write three symphonies and two overtures, but attracted most attention for her chamber music. The latter included two works for unusual combinations, perhaps inspired by her studies with Reicha, the master of the wind quintet: a sextet for wind quintet and piano, and a nonet for wind quintet and strings (violin, viola, cello, double bass). The nonet was an overnight sensation at its premiere in 1850, which was led by the young but already famous Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim, a protégé of Mendelssohn visiting Paris. Following the premiere, Farrenc approached the director of the Conservatoire to point out that she was being paid considerably less than her male colleagues. It was not the first time she’d raised the issue, but the success of the Nonet meant the director couldn’t ignore it, and he raised her salary to match.

Louise Farrenc’s most gifted piano student was her daughter Victorine, and Victorine’s death at age 32 in 1859 was a heavy blow. Louise threw herself into a project of reviving earlier keyboard music, publishing an impressive multi-volume work over several years called Le trésor des pianistes. Especially fascinating for present-day performers of early music, she led a series of concerts in which she and her pupils performed music by 17th- and 18th-century composers, and published a treatise on historical performance practice. The concerts were referred to as séances historiques, as they called up the spirit of composers of another time through their music.

Connections

- Mendelssohn wrote his Octet shortly after a trip to Paris in 1825, and it seems likely that that he and Farrenc would have met at Reicha’s studio: Farrenc was Reicha’s long-time pupil, and the younger Mendelssohn studied with Reicha while he was there. This concert offers a musical reunion, just shy of 200 years later.

- The Hungarian violinist Joachim made his London debut at age 12, playing the Beethoven concerto. The concerto was conducted by Beethoven’s friend, Felix Mendelssohn, Joachim’s mentor in Leipzig. A few years after Mendelssohn’s death, a 19-year-old Joachim led the premiere of Farrenc’s Nonet in Paris. Joachim championed Mendelssohn’s works throughout his life, and somewhat inadvertently assured Farrenc’s international renown, as the Nonet played a large part in establishing her renown in Europe.

- Both Mendelssohn and Farrenc undertook study of “early music,” Mendelssohn delving into the works of Bach and Handel, and Farrenc into the study of keyboard music from Frescobaldi to Mozart. They taught this music to their students at the conservatories in Leipzig and Paris respectively. The last pieces included in Farrenc’s 20-volume Trésor des pianistes are two piano works by Felix Mendelssohn.

Thank You to our Generous Donors

Tafelmusik is deeply grateful to our generous donors who have continued to support us through this challenging time. Your support has inspired us to remain strong and to deliver joy to our community through our music, and will enable us to persevere until we can once again perform live for you, our cherished patrons. Thank you for believing in Tafelmusik and in the power and beauty of music.

If you would like to make a gift, please click here or contact us at donations@tafelmusik.org.

Thank you to our government sponsors