Hélène Brunet, soprano

Cecilia Duarte, mezzo-soprano

Charles Daniels, tenor

Jesse Blumberg, baritone

Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra & Chamber Choir

Directed by Ivars Taurins

Live performances:

November 22–24, 2024 at Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St. Paul’s Centre

Program

Part I

Feria 1 Nativitatis Christi

For the First Day of Christmas

Part II

Feria 2 Nativitatis Christi

For the Second Day of Christmas

INTERMISSION

Part III

Feria 3 Nativitatis Christi

For the Third Day of Christmas

Part V & VI

Dominica post Festum Circumcisionis Christi / Festo Epiphanias

For the Sunday after New Year’s Day / For the Feast of Epiphany

Hélène Brunet, soprano

Hélène Brunet is recognized for her interpretations of Bach, Handel, and Mozart, her repertoire extending from baroque to the music of the 20th and 21st centuries. She is the recipient of a prestigious JUNO Award (2022) for her first solo album Solfeggio with the renowned ensemble L‘Harmonie des saisons. Hélène is the first artist to ever win for a solo album in the Large Ensemble category at the JUNOs. Accolades continue with Solfeggio being selected as one of CBC Music’s Top 20 Classical albums of the year. On the stage, Hélène sings with the American Classical Orchestra at Lincoln Center in New York City, American Bach Soloists in San Francisco, and Orchestre Métropolitain under the baton of Yannick Nézet-Séguin.

Cecilia Duarte, mezzo-soprano

Born in Chihuahua, Mexico, Cecilia Duarte is a versatile singer who has performed around the world singing a variety of music styles, with special emphasis on early and contemporary music. She has premiered roles in numerous new operas, including several for Houston Grand Opera. She is widely recognized for creating the role Renata in the Mariachi Opera Cruzar la Cara de la Luna by Martínez, produced across the US as well as in Europe and South America. Cecilia’s early music experience includes appearances with Ars Lyrica Houston, Early Music Vancouver, Pacific Music Works, The Boston Early Music Festival, Mercury Houston, Seraphic Fire, and the Bach Collegium San Diego, among others. Recordings include her first solo album, Reencuentros, and soloist in the Grammy-winning album Duruflé: The Complete Choral Works.

Charles Daniels, tenor

Charles Daniels is a renowned interpreter of baroque music, informed by 12 centuries’ music. His recordings include Bach Passions, Handel Messiah, Monteverdi L’Orfeo and Vespers, and chamber music from Senfl to Tavener. He created the roles of Ulisse / John Dunne in last year’s Bayerische Staatsoper production of Il Ritorno d’Ulisse/Jahr des magisches Denken. Concert appearances include the BBC Proms, De Nederlandse Bach Vereniging, premieres of John Tavener’s Songs of the Sky (Aldeburgh 2007), and Kilar’s Missa Pro Pace (2001) with the Warsaw Philharmonic. Charles’ reconstructions of Gesualdo’s Sacrae Cantiones à 6 were premiered by the Gesualdo Consort of Amsterdam. His completion of Purcell’s Arise my Muse was broadcast on Radio-Canada during the Montréal Baroque Festival. He is delighted to return to Tafelmusik, with whom he has enjoyed a long and happy collaboration.

Jesse Blumberg, baritone

Baritone Jesse Blumberg has performed featured roles at Minnesota Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, Atlanta Opera, Boston Early Music Festival, Opera Atelier, and at Château de Versailles Spectacles and London’s Royal Festival Hall. He has sung major concert works with Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, American Bach Soloists, Boston Baroque, Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, Oratorio Society of New York, The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Early Music Vancouver, and on Lincoln Center’s American Songbook series. Jesse has been featured on nearly 30 commercial recordings, including the 2015 Grammy-winning and 2019 Grammy-nominated Charpentier Chamber Operas with Boston Early Music Festival. He is also the founding Artistic Director of Five Boroughs Music Festival in New York City, and has served as a guest instructor of voice at Cleveland Institute of Music.

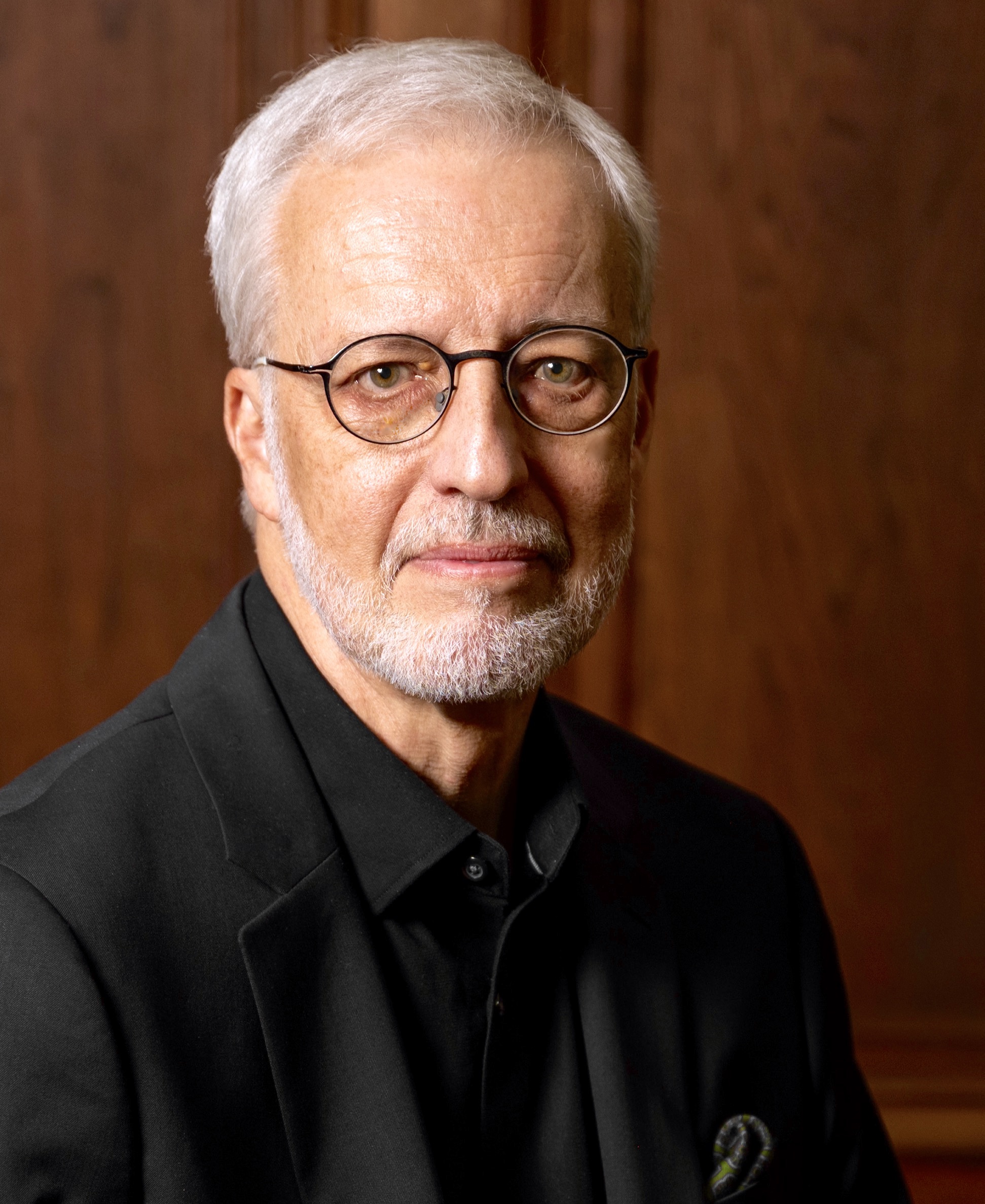

Ivars Taurins, director

Equally at home conducting symphonic and choral repertoire, Ivars Taurins is the founding director of the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir. He was also founding member and violist of the Tafelmusik Orchestra for its first 23 years. Principal Baroque Conductor of the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra from 2001–2011, he appears as guest director with orchestras and choirs across Canada, and is directing the Adelaide Symphony in Australia this season. Ivars was director of the 2012 National Youth Choir, and has directed the Ontario and Nova Scotia Youth Choirs, and London, Calgary, and Nova Scotia Youth Orchestras. A passionate lecturer and teacher, Ivars teaches orchestral conducting at the University of Toronto and Glenn Gould School, and has been a guest teacher/conductor at universities across Canada.

Tafelmusik Chamber Choir

Ivars Taurins, Director

Soprano

Alison Beckwith, Juliet Beckwith, Jane Fingler, Roseline Lambert, Carrie Loring, Lindsay McIntyre, Meghan Moore , Jennifer Wilson

Alto

James Dyck, Kate Helsen, Simon Honeyman, Valeria Kondrashov, Peter Koniers

Tenor

Paul Jeffrey, Will Johnson, Robert Kinar, Cory Knight, Sharang Sharma

Bass

Alexander Bowie, Parker Clements, Paul Genyk-Berezowsky, Nicholas Higgs, Alan Macdonald

Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra

Violin 1

Patricia Ahern, Johanna Novom, Cristina Zacharias

Violin II

Christopher Verrette, Chloe Fedor, Geneviève Gilardeau

Viola

Patrick G. Jordan, Brandon Chui

Violoncello

Keiran Campbell*, Michael Unterman

Double Bass

Jussif Barakat

Flute

Grégoire Jeay, Alison Melville

Oboe & Oboe d’amore

Daniel Ramirez, David Dickey

Oboe da Caccia

John Abberger, Gillian Howard

Bassoon

Dominic Teresi

Trumpet

Kathryn Aducci, Shawn Spicer, Norman Engel

Timpani

Ed Reifel

Organ

Charlotte Nediger

Access full bios for core orchestra members at tafelmusik.org/meet-tafelmusik

*Cello chair generously endowed by the Horst Dantz and Don Quick Fund

Program Notes

By Charlotte Nediger

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was composed in 1734. The title page of the printed libretto, prepared for the congregation, notes “Oratorio performed over the holy festival of Christmas in the two chief churches in Leipzig.” The oratorio was divided into six parts, each part to be performed at one of the six services held during the Lutheran celebration of the Twelve Nights of Christmas. The music would have served as the “principal music” for the day, replacing the cantata that would otherwise have been performed. The structure of the Christmas Oratorio is similar to that of Bach’s Passions: Bach presents a dramatic rendering of a biblical text, largely in the form of sung by an Evangelist to a simple chordal accompaniment. To this is added comments and reflections of both an individual and congregational nature, in the form of arias, choruses, and chorales. The biblical text in question is the story of the birth of Jesus through to the arrival of the three Wise Men, drawn from the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew. The narrative is by its very nature less dramatic than that of the Passions, and Bach introduces a number of arioso passages: accompanied recitatives in which the spectator enters the story. The bass soloist, for example, speaks to the shepherds, and the alto to Herod and to the Wise Men, outside the narrative proper, yet intimately involved with it. The alto—in our performances a mezzo-soprano—sings the most personal, introspective arias, including the beautiful lullaby “Schlafe, mein Liebster” (Sleep, my diearest), in which one can imagine that she is singing as Mary.

Bach supplies each part of the Christmas Oratorio with its own orchestration. Part I opens with the glorious sound of trumpets and drums as all are invited to rejoice in the arrival of the Christ child. Flutes and a quartet of oboes d’amore and oboes da caccia paint a pastoral scene as the angel approaches the shepherds in Part II. The trumpets return to celebrate the shepherds’ arrival in Bethlehem in Part III. Parts IV, V, and VI present the story of the christening of Jesus, the journey of the three Wise Men and their meeting with Herod, and finally their arrival in Bethlehem and presentation of gifts. The narrative is complemented by reflections on the name of Jesus (Part IV), on the Light of Christ and the prophecy of hhis coming (Part V), and on Christ’s victory over his foes (Part VI). A performance of all six cantatas in one evening is too lengthy to be practical, so we have chosen to shorten these reflective portions. We will omit Part IV altogether, and have combined Parts V & VI.

The single most unifying feature of the Christmas Oratorio, apart from the continuous narrative, is in the use of chorales, the distinctive Lutheran hymns. At least two chorales are heard in each part in a variety of settings, from “simple” four-part harmonizations, to chorale-based choruses, to reflective quotes in accompanied recitatives. All of the chorales used by Bach would have been very familiar to the congregations hearing the Christmas Oratorio in 1734. Chorales were fundamental to Lutheran worship, used throughout the church year and sung from memory by the congregation. When hearing chorale melodies in the context of a cantata, oratorio, or Passion, Bach’s audience would have understood their significance on a visceral as well as intellectual level. Listeners today who approach the work from a secular point of view may still experience the chorales as moments of feeling grounded, or moments of affirmation.

Text & Translation

PART ONE

For the First Day of Christmas (Luke 2:1, 3-7)

Coro

Jauchzet, frohlocket! auf, preiset die Tage,

rühmet, was heute der Höchste getan!

Lasset das Zagen, verbannet die Klage,

stimmet voll Jauchzen und Fröhlichkeit an!

Dienet dem Höchsten mit herrlichen Chören,

laßt uns den Namen des Herrschers verehren!

Evangelist

Esbegab sich aber zu der Zeit, daß ein Gebot von dem

Kaiser Augusto ausging, daß alle Welt geschätzet

würde. Und jedermann ging, daß er sich schätzen ließe, ein jeglicher in seine Stadt. Da machte sich auch auf Joseph aus Galiläa, aus der Stadt Nazareth, in das jüdische Land zur Stadt David, die da heißet Bethlehem; darum, daß er von dem Hause und Geschlechte David war: auf daß er sich schätzen ließe mit Maria, seinem vertrauten Weibe, die war schwanger. Und als sie daselbst waren, kam die Zeit, daß sie gebären sollte.

Recitativo (Alto)

Nun wird mein liebster Bräutigam,

nun wird der Held aus Davids Stamm

zum Trost, zum Heil der Erden

einmal geboren werden.

Nun wird der Stern aus Jakob scheinen,

sein Strahl bricht schon hervor.

Auf, Zion, und verlasse nun das Weinen,

dein Wohl steigt hoch empor!

Aria (Alto)

Bereite dich, Zion, mit zärtlichen Trieben,

den Schönsten, den Liebsten bald bei dir zu sehn!

Deine Wangen müssen heut viel schöner prangen,

eile, den Bräutigam sehnlichst zu lieben!

Choral

Wie soll ich dich empfangen

und wie begegn’ ich dir?

O aller Welt Verlangen,

O meiner Seelen Zier!

O Jesu, Jesu, setze

mir selbst die Fackel bei,

damit, was dich ergötze,

mir kund und wissend sei!

Evangelist

Und sie gebar ihren ersten Sohn und wickelte ihn in

Windeln und legte ihn in eine Krippen, denn sie

hatten sonst keinen Raum in der Herberge.

Chorus

Rejoice, exult! rise, glorify the days,

praise what the Most High has done this day!

Leave your fears, banish sorrow,

strike up a song of joy and exaltation!

Serve the Most High with glorious choirs,

let us honour the name of the Lord!

Evangelist

And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed. And all went to be taxed, every one into his own city. And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judaea, unto the city of David, which is called Bethlehem (because he was of the house and lineage of David), to be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child. And so it was, that, while they were there, the days were accomplished that she should be delivered.

Recitative (Alto)

Now my beloved bridegroom,

now the hero of David’s house

will at last be born,

for the solace and salvation of the earth.

Now the star of Jacob will shine,

its rays already break forth.

Rise, Zion, and cease your weeping,

your well-being rises high above!

Aria (Alto)

Prepare yourself, Zion, with tender desires,

the fairest and dearest soon beside you to behold.

Your cheeks must shine all the lovelier today;

hasten to love the bridegroom most ardently.

Chorale

How shall I receive thee,

and how shall I meet thee?

O desired of all the world,

O adornment of my soul,

O Jesu, Jesu, set

the torch near me thyself,

so that which pleases thee

may be known and understood by me.

Evangelist

And she brought forth her firstborn son, and

wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a

manger; because there was no room for them in the inn.

Choral (Soprano) e Recitativo (Bass)

Er ist auf Erden kommen arm,

Wer will die Liebe recht erhöhn,

die unser Heiland vor uns hegt?

Daß er unser sich erbarm,

Ja, wer vermag es einzusehen,

wie ihn der Menschen Leid bewegt?

Und in dem Himmel mache reich,

Des Höchsten Sohn kömmt in die Welt,

weil ihm ihr Heil so wohl gefällt,

Und seinen lieben Engeln gleich.

So will er selbst als Mensch geboren werden.

Kyrieleis!

Aria (Bass)

Großer Herr, o starker König,

liebster Heiland, o wie wenig

achtest du der Erden Pracht!

Der die ganze Welt erhält,

ihre Pracht und Zier erschaffen,

muß in harten Krippen schlafen.

Choral

Ach mein herzliebes Jesulein,

Mach dir ein rein sanft Bettelein,

Zu ruhn in meines Herzens Schrein,

Daß ich nimmer vergesse dein!

Chorale (Soprano) & Recitative (Bass)

He came poor upon the earth,

Who can rightly extol the love

that our Saviour harbours for us?

that he may have mercy on us,

Yea, who can understand

how man’s distress so moved him?

and make us rich in heaven,

The son of the Most High comes into the world

because its salvation pleases him so,

and liken us unto his beloved angels.

that he himself will be born as man.

Kyrie eleison!

Aria (Bass)

Great Lord, oh mighty King,

beloved Saviour, oh how little

dost thou esteem earthly pomp!

He who cares for the entire world,

who created its riches and splendour,

must sleep in a hard manger.

Chorale

Oh my dearest little Jesu,

make for thyself a pure, soft little bed

in which to rest in my heart’s shrine,

that I may never forget thee.

PART TWO

For the Second Day of Christmas (Luke 2:8-14)

Sinfonia

Evangelist

Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend auf dem

Felde bei den Hürden, die hüteten des Nachts ihre

Herde. Und siehe, des Herren Engel trat zu ihnen, und

die Klarheit des Herren leuchtet um sie, und sie

furchten sich sehr.

Choral

Brich an, o schönes Morgenlicht,

und laß den Himmel tagen!

Du Hirtenvolk, erschrecke nicht,

weil dir die Engel sagen,

daß dieses schwache Knäbelein

soll unser Trost und Freude sein,

dazu den Satan zwingen

und letztlich Friede bringen!

Evangelist

Und der Engel sprach zu ihnen:

Engel

Fürchtet euch nicht, siehe, ich verkündige euch große

Freude, die allem Volke widerfahren wird. Denn euch

ist heute der Heiland geboren, welcher ist Christus,

der Herr, in der Stadt David.

Recitativo (Bass)

Was Gott dem Abraham verheißen,

das läßt er nun dem Hirtenchor erfüllt erweisen.

Ein Hirt hat alles das zuvor von Gott erfahren müssen.

Und nun muß auch ein Hirt die Tat,

was er damals versprochen hat,

zuerst erfüllet wissen.

Aria (Tenor)

Frohe Hirten, eilt, ach eilet,

eh ihr euch zu lang verweilet,

eilt, das holde Kind zu sehn!

Geht, die Freude heißt zu schön,

sucht die Anmut zu gewinnen,

geht und labet Herz und Sinnen!

Evangelist

Und das habt zum Zeichen: Ihr werdet finden das Kind in Windeln gewickelt und in einer Krippe liegen.

Sinfonia

Evangelist

And there were in the same country shepherds

abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock

by night. And lo, the angel of the Lord came upon

them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about

them: and they were sore afraid.

Chorale

Break forth, oh lovely morning light,

and let the heavens dawn!

Ye shepherd folk, be not afraid,

for the angels tell you

that this weak babe

shall be our comfort and joy,

there to subdue Satan

and bring peace at last.

Evangelist

And the angel said unto them:

Angel

Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of

great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you

is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which

is Christ the Lord.

Recitative (Bass)

That which God promised Abraham he now fulfils

and lets it be known to the band of shepherds.

A shepherd had to learn all this before from God,

and now also must a shepherd

first know the act fulfilled,

which he had promised.

Aria (Tenor)

Joyful shepherds, make haste,

hasten lest ye tarry too long,

hasten to see the lovely child.

Go, the joy is all too wonderful,

seek to gain grace,

go and refresh heart and mind.

Evangelist

And this shall be a sign unto you; Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.

Choral

Schaut hin, dort liegt im finstern Stall,

des Herrschaft gehet überall!

Da Speise vormals sucht ein Rind,

da ruhet itzt der Jungfrau’n Kind.

Recitativo (Bass)

So geht denn hin, ihr Hirten, geht,

daß ihr das Wunder seht:

und findet ihr des Höchsten Sohn

in einer harten Krippe liegen,

so singet ihm bei seiner Wiegen

aus einem süßen Ton

und mit gesamtem Chor

dies Lied zur Ruhe vor!

Aria (Alto)

Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh,

wache nach diesem vor aller Gedeihen!

Labe die Brust,

empfinde die Lust,

wo wir unser Herz erfreuen!

Evangelist

Und alsobald war da bei dem Engel die Menge der

himmlischen Heerscharen, die lobten Gott

und sprachen:

Chorale

Behold, there in a dark stable lies

the one whose majesty encompasses all!

Where once an ox sought food,

there now rests the virgin’s child.

Recitative (Bass)

So go then hence, ye shepherds,

go, that ye may see the miracle;

and if ye find the son of the Most High

lying in a hard manger,

then sing to him by his cradle

in a sweet voice

and with full choir,

sing this lullaby.

Aria (Alto)

Sleep, my dearest, enjoy thy rest,

and awaken then that all may flourish!

Refresh thy breast,

experience the delight,

there where we gladden our hearts!

Evangelist

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude

of the heavenly host praising God, and saying:

Coro: Die Engel

Ehre sei Gott in der Höhe und Friede auf Erden

und den Menschen ein Wohlgefallen.

Recitativo (Bass)

So recht, ihr Engel, jauchzt und singet,

daß es uns heut so schön gelinget!

Auf denn! wir stimmen mit euch ein,

uns kann es so wie euch erfreun.

Choral

Wir singen dir in deinem Heer

aus aller Kraft, Lob, Preis und Ehr,

daß du, o lang gewünschter Gast,

dich nunmehr eingestellet hast.

Chorus of Angels

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace,

good will towards all people.

Recitative (Bass)

Then rightly, ye angels, rejoice and sing,

that it is such a wonderful day for us.

Rise then! We will join our voices to yours,

so that we too can rejoice.

Chorale

We sing to thee in thy host

with all our might, praise, honour, and glory,

that thou, oh long-desired guest,

hast now appeared.

PART THREE

For the Third Day of Christmas (Luke 2:15-20)

Coro

Herrscher des Himmels,

erhöre das Lallen,

laß dir die matten Gesänge gefallen,

wenn dich dein Zion mit Psalmen erhöht!

Höre der Herzen frohlockendes Preisen,

wenn wir dir itzo die Ehrfurcht erweisen,

weil unsre Wohlfahrt befestiget steht!

Evangelist

Und da die Engel von ihnen gen Himmel fuhren, sprachen die Hirten untereinander:

Chorus

Ruler of heaven,

hear our stammering tones,

let our feeble singing please thee,

when thy Zion exalts thee with psalms!

Hear our hearts’ triumphant praise,

when we now show our reverence for thee,

because our salvation is assured.

Evangelist

And it came to pass, as the angels were gone away from them into heaven, the shepherds said one to another:

Coro: Die Hirten

Lasset uns nun gehen gen Bethlehem und die

Geschichte sehen, die da geschehen ist, die uns der

Herr kundgetan hat.

Recitativo (Bass)

Er hat sein Volk getröst’,

er hat sein Israel erlöst,

die Hülf aus Zion hergesendet

und unser Leid geendet.

Seht, Hirten, dies hat er getan;

geht, dieses trefft ihr an!

Choral

Dies hat er alles uns getan,

sein groß Lieb zu zeigen an;

Des freu sich alle Christenheit

und dank ihm des in Ewigkeit.

Kyrieleis!

Duetto (Soprano, Bass)

Herr, dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen

tröstet uns und macht uns frei.

Deine holde Gunst und Liebe,

deine wundersamen Triebe

machen deine Vatertreu wieder neu.

Evangelist

Und sie kamen eilend und funden beide, Mariam und Joseph, dazu das Kind in der Krippe liegen. Da sie es aber gesehen hatten, breiteten sie das Wort aus, welches zu ihnen von diesem Kind gesaget war. Und alle, für die es kam, wunderten sich der Rede, die ihnen die Hirten gesaget hatten. Maria aber behielt alle diese Worte und bewegte sie in ihrem

Herzen.

Aria (Alto)

Schließe, mein Herze, dies selige Wunder

fest in deinem Glauben ein!

Lasse dies Wunder, die göttlichen Werke,

immer zur Stärke deines schwachen Glaubens sein!

Recitativo (Alto)

Ja, ja, mein Herz soll es bewahren,

was es an dieser holden Zeit

zu seiner Seligkeit für sicheren Beweis erfahren.

Choral

Ich will dich mit Fleiß bewahren,

ich will dir

leben hier,

dir will ich abfahren,

Mit dir will ich endlich schweben

voller Freud

ohne Zeit

dort im andern Leben.

Evangelist

Und die Hirten kehrten wieder um, preiseten und lobten Gott um alles, das sie gesehen und gehöret hatten, wie denn zu ihnen gesaget war.

Choral

Seid froh dieweil,

daß euer Heil

ist hie ein Gott und auch ein Mensch geboren,

der, welcher ist

der Herr und Christ

in Davids Stadt, von vielen auserkoren.

Coro (bis)

Herrscher des Himmels,

erhöre das Lallen, &c.

Chorus of Shepherds

Let us now go even unto Bethlehem, and see this

thing which is come to pass, which the Lord hath

made known unto us.

Recitative (Bass)

He has comforted his people,

he has delivered his Israel,

sent help out of Zion

and ended our suffering.

Behold, shepherds, this has he done;

go, this is what awaits you!

Chorale

All this has he done for us,

his great love to proclaim;

For this let all Christendom rejoice

and thank him in eternity.

Kyrie eleison!

Duet (Soprano & Bass)

Lord, thy compassion, thy mercy

comforts us and makes us free.

Thy gracious favour and love,

thy wondrous desire

renew thy fatherly devotion.

Evangelist

And they came with haste, and found Mary, and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger. And when they had seen it, they made known abroad the saying which was told them concerning this child. And all they that heard it wondered at those things which were told them by the shepherds. But Mary kept all these things, and pondered them in her heart.

Aria (Alto)

Enclose, my heart, this blessed wonder

fast within thy faith.

Let this miracle, these divine works,

ever be the strength of thy weak faith!

Recitative (Alto)

Yes, yes, my heart shall cherish that which,

at this auspicious hour, it experiences

as a sure revelation of its salvation.

Chorale

I shall keep thee diligently,

I shall live

for thee here,

I shall depart to thee hence.

With thee shall I soar at last,

filled with joy,

time without end,

there in the other life.

Evangelist

And the shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all the things that they had heard and seen, as it was told unto them.

Chorale

Be joyful meanwhile,

that your salvation

is here born both God and man,

he, who is

the Lord and Christ

in the city of David, chosen of many.

Chorus (repeat)

Ruler of Heaven,

hear our stammering tones, &c.

PART FIVE & SIX

For the Sunday after New Year’s Day (Matthew 2:1-2)

/For the Feast of Epiphany (Matthew 2:7-12)

Coro

Ehre sei dir, Gott, gesungen,

dir sei Lob und Dank bereit’.

Dich erhebet alle Welt,

weil dir unser Wohl gefällt,

weil anheut

unser aller Wunsch gelungen,

weil uns dein Segen so herrlich erfreut.

Evangelist

Da Jesus geboren war zu Bethlehem im jüdischen Lande zur Zeit des Königes Herodis, siehe, da kamen die Weisen vom Morgenlande gen Jerusalem und sprachen:

Coro (Die Weisen) e Recitativo (Alto)

Wo ist der neugeborne König der Jüden?

Sucht ihn in meiner Brust,

hier wohnt er, mir und ihm zur Lust!

Wir haben seinen Stern gesehen im Morgenlande

und sind kommen, ihn anzubeten.

Wohl euch, die ihr dies Licht gesehen,

es ist zu eurem Heil geschehen!

Mein Heiland, du, du bist das Licht,

das auch den Heiden scheinen sollen,

und sie, sie kennen dich noch nicht,

als sie dich schon verehren wollen.

Wie hell, wie klar muß nicht dein Schein,

geliebter Jesu, sein!

Choral

Dein Glanz all Finsternis verzehrt,

die trübe Nacht in Licht verkehrt.

Leit uns auf deinen Wegen,

daß dein Gesicht

und herrlichs Licht

wir ewig schauen mögen!

Evangelist

Da berief Herodes die Weisen heimlich und erlernet mit Fleiß von ihnen, wenn der Stern erschienen wäre? Und weiset sie gen Bethlehem und sprach:

Herodes

Ziehet hin und forschet fleißig nach dem Kindlein, und wenn ihr’s findet, sagt mir’s wieder, daß ich auch komme und es anbete.

Chorus

Let thy glory be sung, oh God,

let praise and thanks be prepared for thee.

All the world exalts thee,

because our welfare is pleasing to thee,

because this day

all our wishes have come to pass,

because thy blessing so gloriously delights us.

Evangelist

Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem,

saying:

Chorus (The Wise Men) & Recitative (Alto)

Where is he that is born King of the Jews?

Seek him in my bosom,

here he dwells, to his and my delight.

For we have seen his star in the east,

and are come to worship him.

Blessed be ye who have seen this light;

it came to pass for your salvation.

My Saviour, thou, thou art the light,

that will also shine upon the heathens,

and they do not yet know thee,

yet they already wish to worship thee.

How bright, how clear, must thy

radiance be, beloved Jesu!

Chorale

Thy splendour consumes all darkness

and transforms the gloomy night to light.

Lead us in thy ways,

that we may ever behold

thy countenance

and glorious light!

Evangelist

Then Herod, when he had privily called the wise men, enquired of them diligently what time the star appeared. And he sent them to Bethlehem, and said:

Herod

Go and search diligently for the young child; and when ye have found him, bring me word again, that I may come and worship him also.

Recitativo (Soprano)

Du Falscher, suche nur den Herrn zu fällen,

nimm alle falsche List,

dem Heiland nachzustellen;

der, dessen Kraft kein Mensch ermißt,

bleibt doch in sichrer Hand.

Dein Herz, dein falsches Herz ist schon,

nebst aller seiner List, des Höchsten Sohn,

den du zu stürzen suchst, sehr wohl bekannt.

Aria (Soprano)

Nur ein Wink von seinen Händen

stürzt ohnmächtger Menschen Macht.

Hier wird alle Kraft verlacht!

Spricht der Höchste nur ein Wort,

seiner Feinde Stolz zu enden,

O, so müssen sich sofort

sterblicher Gedanken wenden.

Evangelist

Als sie nun den König gehöret hatten, zogen sie hin. Und siehe, der Stern, den sie im Morgenlande gesehen hatten, ging für ihnen hin, bis daß er kam und stund oben über, da das Kindlein war. Da sie den Stern sahen, wurden sie hoch erfreuet und gingen in das Haus und funden das Kindlein mit Maria, seiner Mutter, und fielen nieder und beteten es an und täten ihre Schätze auf und schenkten ihm Gold, Weihrauch und Myrrhen.

Recitative (Soprano)

False one, you seek only to destroy the Lord,

and use every deceitful ruse

to stalk the Saviour;

yet he whose strength no man can measure,

remains in safe hands.

Your heart, your false heart, along with all its deceit,

is already very well known to the son of the Most

High, whom you seek to crush.

Aria (Soprano)

A mere wave of his hands

casts down the might of impotent man.

Here all strength is derided!

The Most High has but to speak a word

to bring an end to the pride of his enemies;

O, thus at once must the thoughts

of mortal men be turned.

Evangelist

When they had heard the King, they departed; and lo, the star, which they saw in the East, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy. And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him; and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts: gold, and frankincense, and myrrh.

Choral

Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier,

O Jesulein, mein Leben;

Ich komme, bring und schenke dir,

was du mir hast gegeben.

Nimm hin! Es ist mein Geist und Sinn,

Herz, Seel und Mut, nimm alles hin,

und laß dirs wohlgefallen!

Evangelist: Und Gott befahl ihnen im Traum, daß sie sich nicht sollten wieder zu Herodes lenken, und zogen durch einen andern Weg wieder in ihr Land.

Recitativo (Tenor)

So geht!

Genug, mein Schatz geht nicht von hier,

er bleibet da bei mir,

ich will ihn auch nicht von mir lassen.

Sein Arm wird mich aus Lieb

mit sanftmutsvollem Trieb

und größter Zärtlichkeit umfassen;

Er soll mein Bräutigam verbleiben,

ich will ihm Brust und Herz verschreiben.

Ich weiß gewiss, er liebet mich,

mein Herz liebt ihn auch inniglich

und wird ihn ewig ehren.

Was könnte mich nun für ein Feind

bei solchem Glück versehren!

Du, Jesu, bist und bleibst mein Freund;

und werd ich ängstlich zu dir flehn:

Herr, hilf!, so laß mich Hülfe sehn!

Recitativo (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass)

Was will der Höllen Schrecken nun,

was will uns Welt und Sünde tun,

da wir in Jesu Händen ruhn?

Choral

Nun seid ihr wohl gerochen

an eurer Feinde Schar,

denn Christus hat zerbrochen,

was euch zuwider war.

Tod, Teufel, Sünd und Hölle

sind ganz und gar geschwächt;

bei Gott hat seine Stelle das menschliche Geschlecht.

Chorale

I stand here by thy cradle,

oh little Jesus, my life;

I come, bring, and give to thee

that which thou hast given me.

Take it! It is my spirit and mind,

heart, soul, and will, take them all,

and may it well please thee!

Evangelist: And being warned of God in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they departed into their own country another way.

Recitative (Tenor)

Go then!

It is enough that my treasure does not go

from here; he remains here with me;

neither will I suffer him to leave me.

His arm will enfold me out of love

with gentle desire

and greatest tenderness.

He shall remain my bridegroom,

I will bequeath him my heart and bosom.

I know with certainty that he loves me,

my heart loves him too, deeply,

and will ever honour him.

What sort of enemy could do me harm

with such good fortune?

Thou, Jesu, art and shalt remain my friend,

and were I to implore thee in fear,

“Lord, help me!” then let me behold thy help!

Recitative (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass)

What now of the terrors of hell?

What can the world and sin do to us,

since we rest in Jesu’s hands?

Chorale

Now are ye well avenged,

upon the host of your enemies,

Christ has shattered

that which was against you.

Death, devil, sin, and hell

are diminished once and for all,

the human race has its place at God’s side.