Program notes by Dominic Teresi, bassoon

The premiere of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail was advertised in Vienna on July 16, 1782. Just four days later the young composer wrote to his father in Salzburg: "Now I have no small task: by Sunday week I have to arrange my opera for wind band, otherwise someone will step in front of me and take the profit.”

The wind band, called a Harmonie at the time, was a particularly popular chamber ensemble in the 18th century, especially at court, responsible for providing dinner music (“Tafelmusik”) and other courtly entertainments. Even noblemen who could not afford to maintain a complete orchestra retained at least a Harmonie. Its repertoire consisted of arrangements of the latest hits from popular operas as well as original works, and it was a principal way in which many people heard music in that time.

Early formations of Harmonies were comprised of a sextet of wind instruments in pairs, the nucleus of which were the horns and bassoons, complemented by a pair of oboes or clarinets in the upper voices. By 1782 the octet formation or “Full Harmonie,” consisting of oboes, clarinets, horns, bassoons, and often a double bass, became standardized by Emperor Joseph. The Emperor’s Harmonie was a fully professional ensemble consisting of virtuoso musicians from the Burgtheater Orchestra, including the clarinettist Anton Stadler, for whom Mozart wrote his clarinet quintet and concerto.

Among the most prolific arrangers for wind band was the Bohemian composer and oboist Johann Nepomuk Wendt. Wendt played second oboe in the Burgtheater Orchestra, and was a member of the Emperor’s elite Harmonie. He transcribed over 50 operas, including Mozart’s Cosí fan tutte, from which we have drawn a selection. [Wendt did not include the aria “Soave sia il vento” is his arrangements from Cosí fan tutti, and yet it is a particular favourite of our players, so we’ve inserted a modern arrangement by the German composer Andreas Tarkmann.]

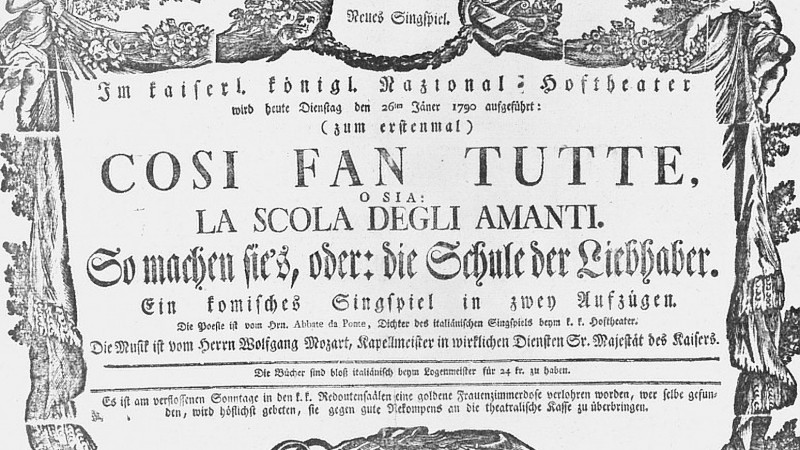

Playbill from premiere of Così fan tutte

In addition to transcriptions, composers wrote a significant amount of original music for wind bands. Mozart’s own contribution to the genre includes numerous divertimentos for two to six winds in various combinations written primarily for the Salzburg court, as well as the three crown jewels of the Harmoniemusik repertoire: two serenades for wind octet, and the Gran Partita for 13 instruments.

“At eleven o'clock at night I was treated to a serenade performed by two clarinets, two horns, and two bassoons — and that of my own composition. These musicians asked that the street door might be opened and, placing themselves in the centre of the courtyard, surprised me, just as I was about to undress, in the most pleasant fashion imaginable.” —W. A. Mozart in letter to his father (November 3, 1781)

“During the summer months, if the weather is fine, one can encounter a serenade in the street any day and at any time of day, possibly at one o'clock in the morning or even later. These serenades, however, do not consist merely of a vocalist accompanied by a guitar, mandora, or similar instrument, as is the practice in Italy or Spain; here serenades are not performed in order to express one's sighs or declare one's love, for which there are a thousand more comfortable opportunities; these serenades consist rather of quartets, quintets or sextets performed by wind instruments. These performances at night show clearly how widely and intensely music is loved; no matter how late at night it may be, even at an hour at which everyone is hurrying home, people may soon be observed at their windows, and in a few minutes the musicians are surrounded by a crowd of listeners, who applaud, frequently demanding that a piece be repeated, as though they were in the theatre, rarely departing until the serenade is concluded and often accompanying the band in large numbers to another part of the town.” —Theatre Almanac (Vienna, 1794)

Mozart’s Serenade in C Minor departs from convention in both its minor mode (the only serenade or divertimento Mozart wrote in a minor key) as well as its formal construction. While serenades typically have five to seven movements mostly based on dance forms, K. 388 is in four movements and is somewhat akin to a symphony for wind instruments. Mozart clearly loved to write for winds and was unparalleled in his ability to exploit the colours these instruments added to his orchestral palate. Indeed, Mozart's Harmoniemusik, most of which was written in his youth, may well have served as the experimental vehicle for working out the wind writing that later became so prominent in his symphonies, concertos, and operas. It is clear that Mozart held the C Minor Serenade in high regard, for he transcribed it himself for string quintet (K. 406). We can also hear a reworking of the principal theme of the slow movement in Mozart's aria “Secondate, aurette amiche” from Cosí fan tutte.

On August 8, 1809, Beethoven wrote to the Leipzig publishers Breitkopf & Härtel, offering several works for publication, including his Wind Sextet, op. 71: “The sextet is one of my earlier things, and, moreover, was written in a single night.” We should probably take with a grain of salt Beethoven's claim to have written his sextet in a single night, since early sketches for the work survive. It was probably written in 1792, shortly after Beethoven arrived in Vienna. It makes sense that in an effort to gain recognition in his new home, some of his earliest efforts would include writing Harmoniemusik. It is telling that by 1809, although Beethoven was at the height of his compositional activity and had already completed his first five symphonies as well as the middle string quartets, he still felt his sextet worthy of publication.

The Rossini arrangement we are performing this week is by Bohemian composer and clarinettist Wenzel Sedlak, who was a prominent soloist in Vienna and an employee of Prince Liechtenstein. In the generation after Wendt, Sedlak was Vienna's foremost exponent of the art of creating transcriptions for Harmonie for some 25 years. Over 60 of his works survive, including several arrangements from operas by Beethoven, Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti.

Cecilia Livingston introduces Gone with the Winds

Taking its title from the title of this program, this piece is a bit tongue-in-cheek: it plays with the repeated note figures of Mozart's K.388 and Beethoven's op. 71 (also on this program), but pushes those gestures into more recent minimalist musical worlds, while hinting at the famous “Tara's Theme” from Max Steiner's score for Gone with the Wind. Laura Millard's artwork Contrails, which Tafelmusik chose to complement this program, suggests the lightness I hope my piece will offer too. Tafelmusik's program for this concert takes the Harmonie ensemble, with its juke-box covers of popular opera music, as a point of departure; Steiner had formative experience conducting opera and operetta, and his score for this gloriously “operatic” (melodramatic) movie, with such a very appropriate title, offered an irresistible musical joke for the end of the piece.

Get to know Cecilia Livingston here.

Image Credits

Contrails by Laura Millard.