This season we have been exploring the theme of music as resistance and the ways in which music has given voice to those who have been chronically underrepresented. In 17th-century Europe —and still to this day— that group of people includes female composers.

Laury chose to focus on Antonia Bembo, the remarkable Italian baroque composer who created her own musical language during her self-imposed exile in France. Laury’s article includes links to several audio excerpts from Bembo’s work The Seven Psalms of David, set to text by the French poet Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron.

Laury directs these performances by La Donna Musicale with soprano Sherezade Panthanki and tenor Aaron Sheehan, who have both appeared as guest soloists with Tafelmusik.

Celebrate International Women’s Day with this guided listening tour curated by one of the world’s foremost experts in the field!

Antonia Bembo: The Resistant Exile

by Laury Gutiérrez

A baby girl named Antonia is born in Venice around 1640. Her father, Giacomo Padovani, is a doctor. Recognized as musically inclined, she is taking lessons in 1654 with Francesco Cavalli, a prominent composer in the city, and eventually the most important Italian composer of early opera.

That same year, the envoy from Mantua mentions Antonia in letters as “the girl who sings.” The envoy wonders if she might be employed at the Mantuan Court. He also reports that her father “falls into a frenzy” and she “suffers from fainting fits brought on by frenetic fears of her father.” The envoy understands that she has been given in marriage to the celebrated guitarist Francesco Corbetta, who had been working in Mantua. Whether that is true or not, in 1659 Antonia is married to a Venetian nobleman, Lorenzo Bembo.

Her marriage is unhappy, so she resists. In 1672, she files for divorce on several grounds, including physical abuse. She loses the case, so she resists once more.

The Italian immigrant

Leaving behind her three young children, causing a scandal and her own heartbreak, Antonia departs for France. Louis XIV hears her sing and awards her a pension. She takes shelter in a convent, which is given in 1683 to the Filles de Saint-Chaumond, an educational institution for women founded by Saint Vincent de Paul. She remains there until her death at an advanced age.

The resistant girl who sang, the student of Cavalli, became the penitent woman who composed in her own mixed French-Italian style.

What was it like for Antonia to leave her children and abandon her known life, to settle in a foreign country, where she was obliged to learn a new language, a new set of social conventions, and a new style of music, ultimately creating her own passionate style of music? A few hints emerge from the music itself, which speaks of resilience, a desire for salvation, and a need to create. The resistant girl who sang, the student of Cavalli, became the penitent woman who composed in her own mixed French-Italian style: for herself, her peers, and now us.

The music itself speaks of resilience, a desire for salvation, and a need to create.

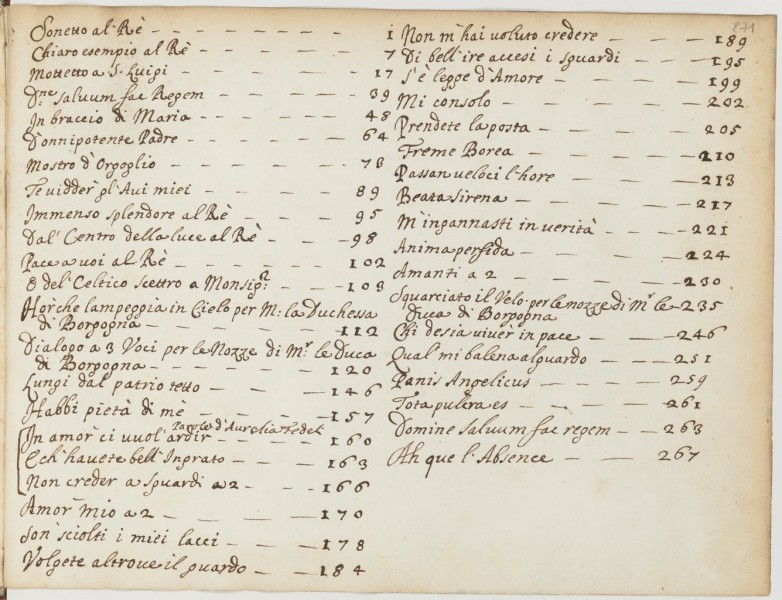

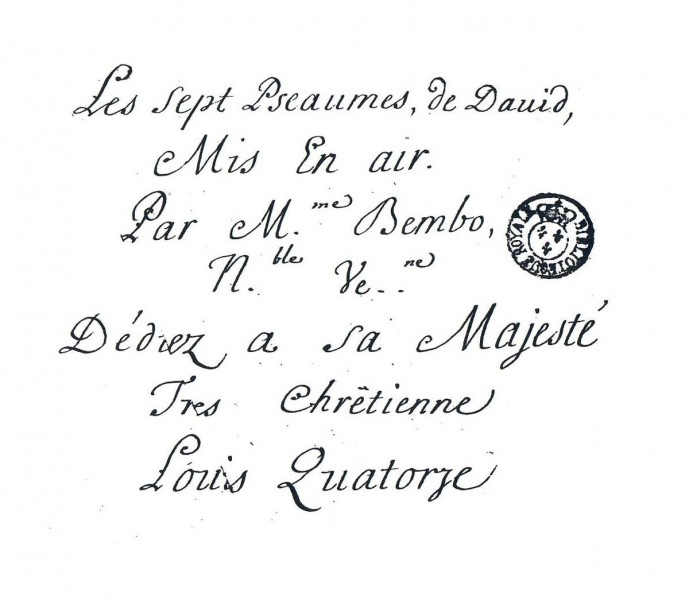

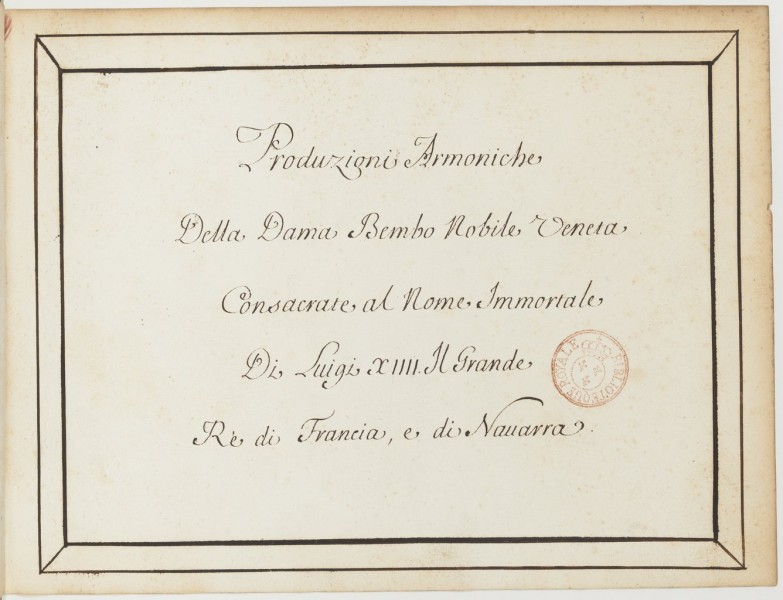

Her testimony lives at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, where I had the privilege of examining her manuscripts: a vocal collection called Produzioni armoniche; two settings of the Te Deum; a five-voice Divertimento; psalm settings; and an opera, Ercole amante, whose libretto by Francesco Buti was also used by Cavalli. Her works were dedicated to Louis XIV, except for two selected for Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie, the Dauphin’s wife. In them we see the transformation of her identity from Antonia, in Produzioni armoniche, to Antoniette, as she signs her French-language psalm settings.

Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron

Let us digress for a moment to introduce you to another extraordinary woman, Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron, who circumvented her inability to publish poetry by enlisting the help of her brother, a publisher.

Self-Portrait by Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron, 1672

The Essay de pseaumes et cantiques mis en verse, et enrichis de figures was published in 1694. The author, Elisabeth-Sophie Chéron (1648–1711), was identified in this publication only as “Mademoiselle ***.” She was a writer, musician, and painter, who had the rare honour of being elected to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.

The magnificent creativity of these two courageous women come together to produce an astonishing work.

Cheron’s paraphrase from Hebrew of The Seven Penitential Psalms (Pseaumes de la penitence) serves as the text for Antonia Bembo’s Les sept Pseaumes de David. Here the magnificent creativity of these two courageous women, the composer Bembo and the poet Chéron, comes together to produce an astonishing work.

Chéron’s text was not the first time Antonia set music to a woman’s words. In Produzione armoniche, she set poetry by the Italian writer Aurelia Fedeli. We have no record, although we can imagine that Antonia met Fedeli, Chéron, and her contemporary women composers Barbara Strozzi (who also studied with Cavalli) and Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre.

I invite you now on a little tour of Antonia’s music, focusing on excerpts from her psalms.

The Seven Psalms of David

According to tradition, the psalms were written by the Biblical figure, King David. In the sixth century, the monk Cassiodorus singled out the psalms that acknowledge David’s sins and his hope for God’s forgiveness as The Seven Penitential Psalms.

These psalm settings are extraordinary because Antonia expresses the nuances of the text as if she herself were asking for forgiveness. The music moves forward relentlessly, with few pauses. The use of dotted against undotted rhythms creates an unsettled impression. The subtle, complex changes of metre closely follow her understanding of the meaning and dramatic content of the text. In her harmony, the affects (emotional colors) are often depicted by unusual and dissonant chords and fascinating modulations. She employs considerable chromaticism, unresolved dissonances, and cross-relations. She does not shy away from parallel fourths and fifths (forbidden in that period) or from angular writing for the instruments. Truly, she creates her own musical language.

As was common in the period, the vocal line in all seven Psalms is accompanied by the basso continuo (keyboard/chordal instruments and viola da gamba/cello) along with one or two treble instruments throughout. The treble instruments function as melodic lines, forming a duet or trio with the singers, or else as harmonic support in a type of “treble continuo,” with frequent “unvocal” leaps.

The intense drama and pathos of some of these psalm settings are reminiscent of an opera

The wide vocal ranges have effective but unusual voice-crossings. For example, the bass or tenor moves into the highest range while the soprano is low. Even a single verse can be subject to several changes of meter. Interpreting the relationship of one section and texture to the next while maintaining a coherent pacing for the entire piece is one of the challenges of performing these psalms. The intense drama and pathos of some of these psalm settings are reminiscent of an opera: quasi-recitative interspersed with “arias.”

Embedded below are recorded excerpts from performances by La Donna Musicale. The ornamentation used is based on French performance practice of the period.

Psalm 50: Miserere mei Deus secundum

At times this setting sounds like an accompanied recitative, at others, an aria with obbligato parts. In the sample section, Je t´eusse offert Seigneur, the voice of Sherezade Panthanki conveys the poetry pleading for forgiveness.

This psalm is scored for two treble voices. The ritournelle marked “gay” (lively) in the section C’est ta grace Seigneur where the video excerpt begins is one ofthe most playful in the Seven Psalms. A phrase from the first ritournelle is used to great effect throughout: initially presented by the violins, thereafter sung to the text “I suffer pain,” appearing again at the beginning of a later verse, and fully developed in the last section, which serves to prepare the listener for the final plea for salvation.

Psalm 31: Beati quorum remissae sunt iniquitates (part one)

Beati quorum remissae sunt iniquitates (part three)

Starting in gentle triple metre, this psalm is unique in that it is in a major key (A major), with modulations to minor keys These choices create the affect for the text "Heureux celuy dont les fautes passée" (“Happy are they whose past faults are erased”)—and even happier are those who are forgiven by God. This psalm is also the only one for four voices, with two treble instruments and continuo. The middle voice in the alto clef is sung here by Aaron Sheehan at pitch, following France’s tradition of high tenors.

Ritournelles separate the verses and often foreshadow the affect of the following section. The bareness of the confession and the high tessitura of the basso continuo line inspired us to perform it with strings alone and no chordal accompaniment. Once the singing begins, the keyboard instruments come in progressively as David confesses his sins.

In conclusion, allow me to share two personal experiences of how Antonia’s music affects people today. A musician commented about Psalm 37: “I think the piece is terrible and it’s going to consume a lot of rehearsal time trying to make sense out of it.” Then, at one of our concerts, a woman raised her hand eagerly and said, “I completely understand this music and Antonia Bembo. You see, I am bipolar, and those fluctuations are a constant in my life.”

Passionate reactions, pro and con. What do you think?

Praised as a “first-rate” instrumentalist by the Boston Globe, Laury Gutiérrez holds degrees from Indiana University and Longy School of Music and has also received fellowships and a scholarship from Boston University, where she did doctoral work in historical performance. She is the founder and director of La Donna Musicale, an internationally acclaimed ensemble that specializes in the performance of early music by women composers. She is also founding director of Rumbarroco, a Latin-Baroque fusion ensemble. Ms. Gutiérrez has been a Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University, and she is a resident scholar at the Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center.

To hear more samples of music by Antonia Bembo, visit her Vimeo channel La Donna/Rumbarocco.

For more information about Antonia Bembo: Dr. Claire Fontijn of Wellesley College has done a remarkable job of compiling everything known about Antonia’s life and historical background. Her book Desperate Measures: The Life and Music of Antonia Padoani Bembo (2006), is a landmark biography and study about this fascinating composer.

To learn more about the music of the other female composers mentioned in the article: Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre and Barbara Strozzi.

Image credit: Gutiérrez by Laury Gutiérrez