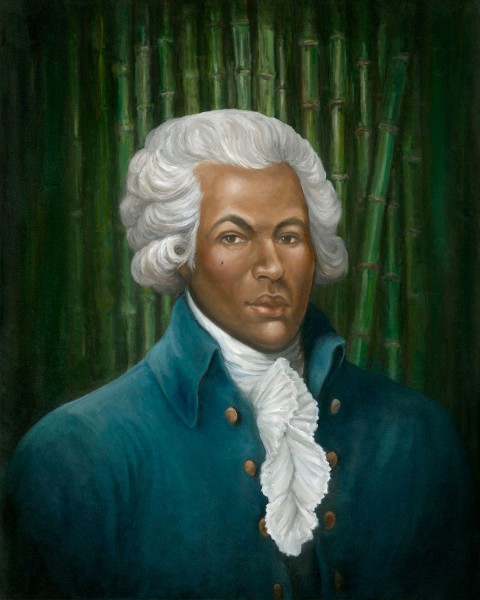

This week, we unveiled Gordon Shadrach’s Opus 7: a brand-new portrait of 18th-century Black composer Joseph Bologne. This portrait will serve as the cover art of our reissued digital album, The Music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

Opus 7 by Gordon Shadrach

Based in Toronto, and born and raised in Brampton, Ontario, Shadrach has exhibited in solo and group art shows in Canada and the United States, and works from photographs at his in-home studio. In this interview, get to know Shadrach, his work, and his relationship to this project.

Artist Gordon Shadrach. Photo by Aous Poules.

Had you heard of Joseph Bologne and his music prior to this collaboration with Tafelmusik?

Gordon Shadrach: I had not heard of Joseph Bologne and his music prior to working with Tafelmusk. Given that I am aware of a number of other composers of the era, I think this links to the lack of representation of his music and the erasure of Black achievements and abilities.

Can you speak a little bit about your process, in creating this portrait of Bologne? Did you research him, or listen to his music, while in the process of creating it?

GS: When I was approached about the project I went on a fact-finding mission. I watched a documentary about him and enjoyed listening to his music. The challenge was finding visual representations of him that offered insights into who he really was as a person. I also wanted to better understand the historical style of the period when he was composing so I researched the fashions of the time.

In your practice, you explore the semiotics of clothing — in particular, the intersection and codification of race and fashion, and with a focus on Black men. Can you expand a little bit more on how depictions of fashion can complicate, disrupt, and/or correct biases of racism, and why and how you address this through your work?

GS: The intersections of race and fashion are complicated and long standing. My fascination with the codification of clothing, dress and style started at an early age because as a young Black boy, I realized that often I was not being judged based on the content of who I am but rather on the colour of my skin and how I presented myself physically to the world. This included not just the clothing I wore, but also the style and length of my hair or the type of shoes I wore.

Historically, painted portraits that were commissioned and the ones we see in museums were of white people of means and were constructed to show the sitter’s wealth and stature. Portraits of Black people during this period are rare and they typically depicted figures wearing clothing and styles of their oppressors. It is hard to determine if these portraits represent any true aspects of the sitters or offer glimpses into who they really were.

Your work has also included the use of textiles. Can you expand on this, and on the semiotic ways textiles also operate as symbols?

GS: I have been employing antique textiles and materials in my work that illustrate the types of roles that Black people have played within the capitalist-focused nature of Westernized industrial systems. Incorporating textiles such as fruit-picking sacks and feed and seed bags references the forced labour of Black bodies in the development in Western civilization. I juxtapose these pieces with paintings that examine professional sports and the positioning and values placed on Black bodies in current times.

Can you speak to your experience as a Black Canadian artist, and why it’s important to reflect and explore Blackness and identity through your art?

GS: Many traditional art institutions in Canada have Eurocentric perspectives that don’t represent the broad experiences of the people that have helped to shape the Canadian experience. This approach has led to the underrepresentation, oppression and erasure of many voices. As a Black man, I never saw myself represented in artwork in public institutions and private galleries. Often, representation of Black people in North American culture perpetuated negative stereotypes and tropes which only deepened the roots of systemic racism.

My parents raised me to think critically and question this as I grew up. As my practice developed, my focus has been on creating narratives that I feel connect to my experiences of being Black in Canada. Black culture is not a static monolith, but I feel that I can create work that resonates with people so they can see themselves in my work and realize that our voices deserve to be heard.

You are also involved with Toronto’s Nia Centre for The Arts, which fosters support for Black creators. Can you speak a little bit about the local scene, and how art fosters community for Black creators and makers?

GS: The Nia Centre is amazing for many reasons. First, it bridges all disciplines of the arts, and has created a community space that draws people together. The Centre starts its work with students in middle and high school, to build an interest and works at bringing together various artists in mentorship roles. This is important, because being a Black artist can feel isolating and it is hard to connect with other Black creative people.

There are many contributing factors to this feeling of isolation, including underrepresentation of Black students in creative courses, which leads to many being self-taught in their fields. School is where many people connect with other like-minded people, but that is not the case for many young Black creatives. In many ways, Nia Centre is bridging the gap for emerging artists. Being the first Black cultural centre in Canada, its main focus is to bring the Black arts community together.

In terms of your creative process, with portraiture, do you start with a sketch? Or dive right into working on canvas?

GS: This is a difficult question because it depends on every project.

I usually start with the feelings or emotion that I want imbued in the portrait so I consider everything including the gaze of the sitter, to the colour choice of the background. Sometimes I sketch and layout ideas, or sometimes I just get inspired by the material or a concept and dig right into it. I work from photographs and sometimes during the process of the photo shoot new ideas emerge. I tend to revise as I paint.

What artists (past or present) inspire your work?

GS: I am frequently asked this question and my answer is that because I was exposed to their work as I grew up, I am often inspired by Renaissance painters.

I have always been fascinated by their use of light to create drama. As a self taught painter, I take inspiration from classic paintings, but I do not apply common colour theory when I work. Often, the colour theory that we learn is based on principles of Western art. My experience has been that this does not always easily apply to Black portraiture or photography, because these theories were not created or designed to reflect all skin types.

I am also looking at how we have been taught about colour and how that adds to the systemic stigmatization of all things dark. I purposely paint a lot of my portraits with dark backgrounds as a way to present darkness as a positive element in my work.

There are many artists I admire. I enjoy a lot of contemporary artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley, Devan Shimoyama, Mickalene Thomas, Nick Cave, and Barkley Hendricks.

What current artists should we be paying attention to?

GS: I think it is important to pay attention to the many different art scenes in Toronto’s different communities, as well as what’s happening across Canada. Sometimes, some collectors or art enthusiasts think that BIPOC artists' work only apply to those within the community, but for voices to excel there needs to be broad support. There is such a wide range of art to explore. I am always excited to see what Michele Pearson Clarke, Bushra Junaid, Anique Jordan, Chantal Gibson, and Ishmil Waterman are doing. There are so many amazing artists I could mention!

Do you have any upcoming projects or exhibitions?

GS: I am working on a project that is exploring the journey of the Black Loyalists and it will be presented with gallery United Contemporary in Toronto in the Fall of 2021.

Anything else you’d like to share?

GS: It was an honour to be part of this project!