This season, we have been exploring the theme of music as resistance: the ways in which music has given voice to those who have been chronically underrepresented. Our explorations have included a panel discussion which unpacked how music can push back again persecution, oppression, and injustice; a recent article from Laury Gutiérrez on Antonia Bembo, the remarkable Italian baroque composer who created her own musical language during her self-imposed exile in France; and the remarkable history of Holocaust music and Francesco Lotoro, the man on a mission to catalog it.

In this final article in our Music as Resistance series, musicologist Daniel Zuluaga presents a bird’s eye view of music of the Americas during the colonial period. His essay raises questions and considers the obstacles that emerge when considering the opposing forces of resistance and assimilation.

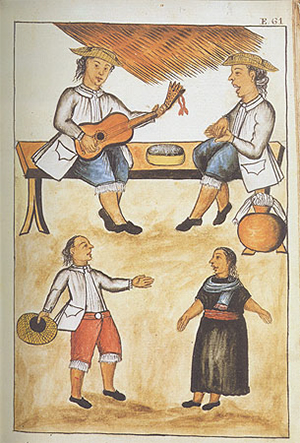

Ydem del Chimo: a watercolor from the Codex Trujillo, or Codex Martinez Compañon

Music and Resistance in Colonial Latin America

By Daniel Zuluaga

For most of the Spanish colonial period in the Americas, musical performance was a core element in the interaction between the continent’s Indigenous populations, imported slave force, and colonizers. Spanish musical traditions were a powerful evangelical tool for the early missionaries. They also represented a link to the homeland for some, a pathway to a new profession for others, and a marker of differentiation through culture, education, and religion, for most of the distinct groups that comprised colonial society.

In addressing the idea of music and resistance in the Americas during the colonial period, there are three major obstacles that concern chronology, geography, and documentation. Let’s start with the chronology. A good number of the urban settlements that became important cultural centres in the colonies, such as Bogotá, Lima, or Puebla, were established as early as the 1530s. On the opposite end, the Spanish colonial period comes to an end, albeit incomplete, in the early 1820s.

These boundaries represent a time frame of nearly 300 years and encompass three well-defined major eras in European music — the Renaissance, Baroque and Classical periods. And yet musical production in the Americas is often misaligned, stylistically speaking, with these eras. It also lags with regard to vanguard trends in Europe, so that in the 1620s, for instance, composers are still writing abundant material that echoes Spanish cancioneros from the mid-to-late sixteenth century rather than, say, monody or early opera.

Partly to make the chronology manageable, researchers have tended to focus on early Spanish-Indigenous musical interactions. More recent studies have examined the later history of such interactions and the assimilation at the urban and rural levels of Spanish musical traditions, uncovering self-sufficient communities, musically speaking, developing separately from Spanish jurisdiction.

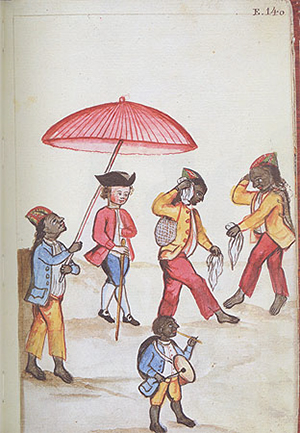

Danza de Bailanegritos

A second obstacle is geography. The region extends from Patagonia in the south to most of what is today the United States. This vast colonial society was underpinned by several key administrative institutions: two sixteenth-century viceroyalties, that of Nueva España, comprising Central and North America, and that of Perú, covering most of South America, expanded in the eighteenth century to include new districts for Nueva Granada (Colombia, Ecuador, Panamá and Venezuela) and Río de la Plata (Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay). Further subdivision into political or religious jurisdictions underscores the Spanish intent to use cities as centres of cultural and economic development and to resettle Indigenous populations into reducciones.

The heterogeneous nature and massive scale of the territory impacted musical culture, whereby the urban entities that are better known to us today are only a partial image of music-making in the continent. Their complement is the largely unscrutinised rural musical culture. Interestingly, it is this heterogeneity which provided the most fertile soil for the active incorporation and successful assimilation of Spanish musical practice into the native communities.

The third obstacle is documentation. One of the main issues in the study of colonial music is the lack of clarity in the geography of music-making in the region. Our current knowledge favours the urban culture over the rural, although that is slowly changing. This is a consequence of better record availability at urban centres, often also linked to the role of the Catholic Church as a main patron of the arts.

Where documentation of another nature survives, there is a sense that music-making was pervasive. For instance, documentation of import duties between 1512 and 1516, charged by customs offices in Puerto Rico to all merchandise brought into the continent, show the regular import of guitars, vihuelas, and instrument strings, pointing to commonplace music-making since the earliest days of the Spanish presence.

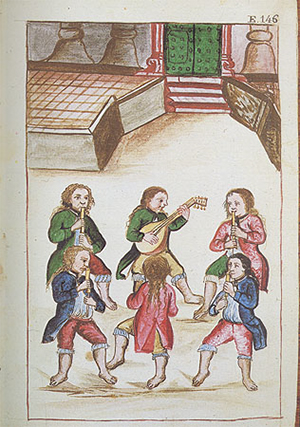

Yden de Carnestolendas

In this context, the idea of resistance in the form of music suggests several questions, none of which is easily answered. How do we engage with the profoundly traumatic aspects of the continent’s history under the Spanish empire? How to interpret the contradictions present in the musical repertoire, where a song text depicting the sorrows of slavery is set to music that invites dancing and singing? What was the perception (and reception) that the different groups, Indigenous, Black, and Spanish, had towards each other’s music?

Currently there are no definitive answers to such questions, but they still allow us to posit some ideas that can help further the conversation. Thanks to the research of musicologists such as Geoff Baker, a key figure in colonial music, we know that the Spaniards’ early view of Indigenous music was tolerant and, if anything, apt to be changed and used for the religious conversion of local populations.

Against the tolerant views stood a cohort that saw Indigenous music and dance as a tool for perpetuating their religious practices, either covertly or out in the open, and sought to ban it. While in theory we get the sense that for every voice that was tolerant, there was another vehemently against it, in practice the result varied by both chronology and geography, with some areas and periods more prone to try to move local populations away from their musical traditions by force, often by repressive churchmen.

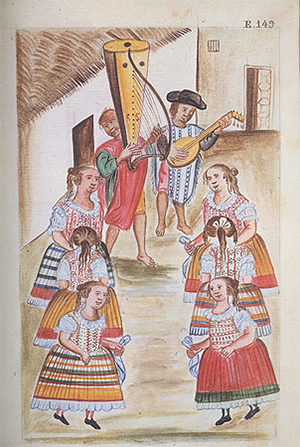

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the music such as that copied by the Spanish bishop Baltasar Martínez Compañón, who in the 1780s, travelled through his archdiocese in Truxillo, in Northern Perú, recording the lives, traditions and music of its inhabitants in nine volumes of watercolours. The few scores he copied succinctly show an amalgam of native and European traditions that undoubtedly reflects living musical practice.

Ydem de Pallas

As to the contradictions, the answer probably lies in developing our awareness as listeners: that many of the surviving songs that seemingly portray rural or local music making more likely reflect musical practice rooted in Spanish institutions and the corresponding performance practice, as appropriated and adapted by local populations. It serves us well to remember that written music presumes at least a medium level of musical literacy, which was more common in the proximity of urban centres.

To the point raised in the first question, we should remember that cultural interaction in the Colonial Americas was not one between equal parties. The Spanish conquest and colonization of the continent, like most endeavours of the sort, was an extremely violent, exploitative process. The main purpose of the colonizers was never other than the economic exploitation of the newly conquered territories and the evangelization of Indigenous populations. Paraphrasing Geoff Baker once again, it is key to keep in mind that when one speaks of colonizers, one also speaks of the colonized, which can be seen as a euphemism for enslavement, oppression, and suffering.

In the popular imagination we still have the tendency to think about music in colonial Latin America as exotic. The evidence points elsewhere: to numerous divergent practices that have strong roots in imported Spanish musical practices. Thus, a clear definition of resistance, at least in this context, remains unattainable.

However, if I were to point to one element that illustrates the idea of music as resistance in the colonial Americas, I would ask the reader to look more closely at the humble guitar. In a sense, this instrument is an embodiment of many of the ideas in this essay, one that has bridged the aforementioned obstacles of chronology, geography, and (lack of) documentation. Its ubiquity in musical practice throughout the entire continent, in urban and rural settings, both then and now, speaks of adaptation, appropriation, and assimilation in a manner that reinforced the development of the distinctive musical practices of the Indigenous, Black, criollo, and Spanish populations in colonial Latin America—populations who took this instrument and made it their own.

Yndios bailando en el Patio de la Chichería

Daniel Zuluaga has made the history and performance practice of early plucked instruments the central tenet of his career as a professional performer and researcher on the baroque guitar, lute, and theorbo. A JUNO Award winner (2016) and a Grammy Award nominee (2018), he is a specialist in Latin American Baroque music. His programming and leadership in the interpretation of this repertoire has earned him numerous critical accolades. He collaborates regularly with leading orchestras in the US and Canada as performer and director, including Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Les Violons du Roy, L’Harmonie des Saisons and Portland Baroque Orchestra. An avid researcher, Mr. Zuluaga holds a PhD in musicology from the University of Southern California and has been recipient of grants and awards from the Fulbright Commission, the American Musicological Society and the Canada Council for the Arts.

Daniel Zuluaga’s recommended recordings for further listening:

- Fiesta Criolla Ensemble Elyma, Gabriel Garrido (K617) on Naxos Music Library and YouTube

- Las Ciudades de oro L’Harmonie des saisons (ATMA Classique) on Spotify and YouTube

- Juan Gutierrez de Padilla Ars longa de la Habana, Teresa Paz (Almaviva) on Spotify and YouTube

- Padilla: Sun of Justice Los Angeles Chamber Singers’ Cappella, Peter Rutenberg, dir. on Spotify

- Codex Martínez Compañón Capilla de Indias, Tiziana Palmeira (K617) on Spotify and YouTube

All images are from the Codex Trujillo, or Codex Martinez Compañon.