Program Notes by Charlotte Nediger

Zelenka Missa Divi Xaverii

Jan Dismas Zelenka was born in 1679 in the Bohemian village of Louňovice, the son of the local choirmaster and organist. He probably received his musical education at one of the Jesuit colleges in Prague, eventually obtaining a post in Prague with the Imperial governor Baron von Hartig. In 1710 he entered the employ of the King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, Friedrich August, in Dresden.

In 1708, much to the alarm of his Protestant subjects, the Catholic elector sought to impress the papal Curia by transforming the former opera house in Dresden into a Catholic church (the Katholische Hofkirche). At first the church led a very discreet existence, with a small number of choristers and instrumentalists imported from Bohemia, including Zelenka. From 1715–1717, the prince travelled to Venice and brought back with him both a company of Italian singers and a new Italian-trained, “modern” Capellmeister, Johann David Heinichen. The Hofkirche flourished, the Dresden public enamoured with the sound of Italian vocal virtuosity and brilliant instrumental writing.

Heinichen’s variable health did not allow him to carry out his duties singlehandedly. He came to depend more and more on Zelenka for assistance. Recruited originally as a rank-and-file double-bass player, Zelenka had high ambitions as a composer. While the Prince was in Venice, Zelenka undertook a period of intensive study under the renowned composition teacher Johann Joseph Fux in Vienna. He was thus able to combine in his works the elaborate counterpoint of the Germans and the Italian influences of the music at Dresden. Add to this his own original and sometimes eccentric use of harmony, and the result is music that is always interesting and often powerful.

Upon Heinichen’s death in 1729, Zelenka may well have expected to take over his post, as he had done the job in all but name for several years. It is not surprising then, that Zelenka would write a mass setting that year that would draw the attention of the court: the Missa Divi Xaverii was first performed December 3, 1729, gloriously scored for an orchestra that included not only the usual oboes, bassoon and strings, but also flutes, four trumpets, and timpani, and described by the Zelenka scholar/conductor Václav Luks as “one of his most dazzling and joyful compositions.”

The occasion was the feast day of St Francis Xavier. He was the patron saint of the Archduchess Maria Josepha (wife of the Crown Prince Friedrich August II), and every child born to her bore the baptismal name of Xavier or Xaveria. Particular care and expense was spent on the celebrations in 1729. The previous year, Maria Josepha’s oldest son and heir had died of smallpox at age seven, and a subsequent pregnancy produced a daughter. The only surviving son was frail and suffered from a spinal condition. Maria Josepha approached her devotions with particular intensity around the 1729 feast day, and Luks points out that a son was born to her nine months later.

If the Missa Divi Xaverii played a small part in promoting Maria Josepha’s cause, it did not gain Zelenka the position at court he had hoped for. He was instead given the title of mere Kirchen-Compositeur (Church Composer), Heinichen’s post of Capellmeister being awarded to an outsider, the popular opera composer Johann Adolf Hasse.

TheMissa Divi Xaverii is a so-called “number mass”: it is divided into distinct movements, including choruses, ensembles, and solo arias. This particular mass does not include a setting of the lengthy Credo text, and yet is a full-length work, giving Zelenka the opportunity to offer fuller settings of the remaining text than is sometimes possible. Like many of his German colleagues, Zelenka used stile misto (mixed style), combining the old and the new, the idiosyncratic with the conventional, the mannered with the well ordered, the operatic with the sacred, and the galant with the Gregorian.

Reconstruction of the score of the Missa Divi Xaverii

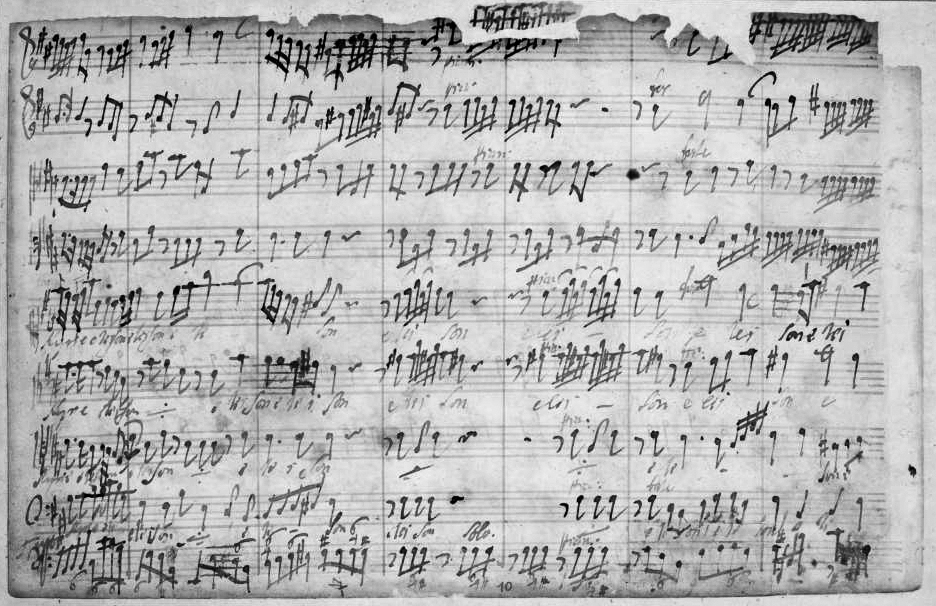

Zelenka's autograph score survives in the Dresden State Library, but the original performing material (33 instrumental and vocal parts) was lost and presumably destroyed at the end of WWII. Zelenka’s scores are infamously difficult to decipher, but this one is particularly so, and some missing information that would have been provided by the parts is irrevocably lost. A further complication is that the damaged tops of the pages of the score were trimmed by an over-zealous librarian at some point, resulting in the top line on many pages being entirely cut off. When the archives of the Berlin Sing-Akademie were returned to Berlin from Kiev in 2001, some incomplete but nonetheless useful copies of the mass were found, making reconstruction possible. This reconstruction was undertaken with great skill by Václav Luks, Artistic Director of the Czech ensemble Collegium 1704, who has championed the works of Bohemian composers, foremost among them, Jan Dismas Zelenka.

A page of the manuscript score of the Kyrie eleison

Bach Magnificat

Johann Sebastian Bach was offered the post of Cantor of the Church of St. Thomas and Director of Music for the town of Leipzig in the spring of 1723. The post was one of the most esteemed positions in Germany during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Bach’s duties in Leipzig were more varied and more demanding than those in any of his previous employs: he was responsible for the music of the four principal Leipzig churches, for the musical education of the students of the Thomasschule, and for all aspects of the town’s musical life as controlled by the town council.

Bach took up his new duties with energy and enthusiasm, and within a few short years had completed four complete cycles of cantatas for the church year, each cycle containing roughly 60 cantatas. From these prolific early years in Leipzig date also several of Bach’s sacred works for special occasions: the great Passions, the motets, and his only Magnificatsetting. The Magnificat text, Mary’s hymn of praise from the Gospel of St. Luke, had been retained from the Roman Catholic Vespers service by the Lutheran reformers. In Leipzig it was sung in German at Sunday afternoon Vesper services. Only on high feast days could Lutheran churches turn to Latin texts, and for the Christmas services at St. Thomas’s in 1723 — Bach’s first Christmas in Leipzig — Bach composed a Latin Magnificat setting. This first version included several Lutheran Christmas hymns, sung in German between the Latin verses. It is a glorious work and must have impressed both the parishioners and the town council. It remained Bach’s only setting of the Magnificat text — when he needed a setting seven years later in 1730 he returned to his original composition, reworking it slightly and removing the German interpolations. It is this second version which is most familiar today, and which we are performing this week.