Download the Program Notes and Program Listing

Program Notes

by Christopher Verrette

Italy in the first quarter of the seventeenth century was the crucible for a new approach toward writing music. The highly debated “new music” took its inspiration in part from impressions of what Ancient Greek theatre may have been like, and sought a more direct appeal to the listener’s emotions and a more fluid attitude toward form than the very rational and structured practices of the renaissance. The old ways were not entirely discarded, however, and remain the cornerstone of a proper education in counterpoint to this day. The first four composers we encounter in the program seem to have one foot in each century.

The violin's versatility made it a natural vehicle for composers in the new form called “sonata” and later the concerto.

The violin was a product of the renaissance and, having already incited many to dancing, was beginning to find its singing voice at the turn of the century. The instrument’s versatility made it a natural vehicle for composers in the new form called “sonata” and later the concerto. Interestingly enough, these same four composers, while making important contributions to the repertoire of the violin, distinguished themselves mostly on other instruments.

Kapsberger is best known for his virtuoso theorbo music, a clear embodiment of the new style, bold and experimental in form and technique. He calls himself a “noble German” on his title pages, and made his way to Rome, where he was a favourite among the musical establishment of the influential Barberini family and hosted “academies” of his own. The sinfonias for ensemble are more restrained in style, and explore different numbers and configurations of instruments without overt virtuosity, as if looking back at where he came from.

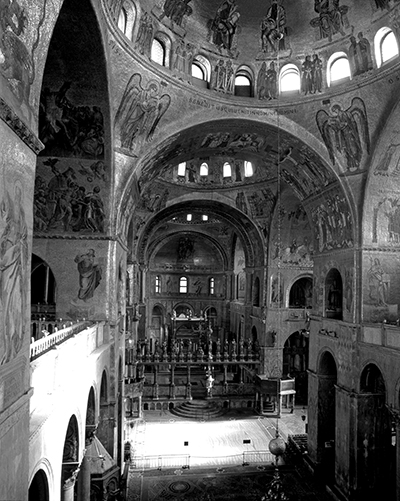

The Canzon Duodecimi Toni is more typical of the Gabrieli style: it is scored for two choirs of instruments that play mostly in alternation, occasionally overlapping or joining forces for a tutti effect. The second choir cheekily makes its entrance in a different metre, bringing on a bit of rhythmic havoc, but order is soon restored. Here the two bass lines are full participants in the rhythms and figures around them, being at times the fastest moving parts.

Samuel Scheidt is regarded as the founder of the North German organ school that included such luminaries as Dietrich Buxtehude and J. S. Bach. Symphonie 7 in D appears in a collection of 70 “Symphonies and Concertos” published in 1644. These concise works, organized by key, appear to be intended to serve as introductions or interludes to other longer pieces, such as dance suites or songs in verses. The long, descending chromatic lines of this symphoniesuggest it would have to be a sad song indeed.

Depictions of battle in music have a long history and inevitably involve many repeated notes at different speeds in imitation of trumpets and drums and general mayhem.

In the Galliard Battaglia, Scheidt cleverly combines the battle idiom with a dance, and thus with love and courtship. The usually playful repeated notes and cross rhythms of the galliard become potentially truly combative in a musical manifestation of the saying “All’s fair in love and war.”

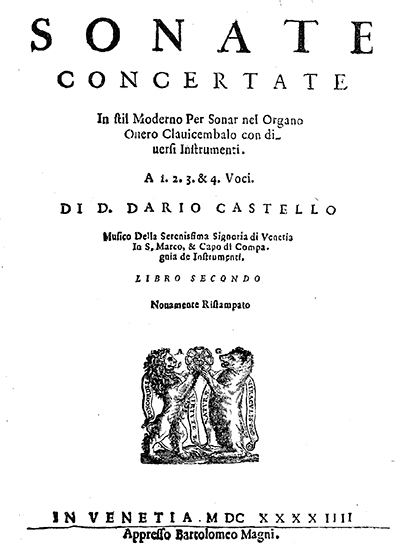

Little is known of the life of Dario Castello other than he was a wind player who worked at San Marco sometime after Gabrieli. His sonatas were clearly popular, as they were reprinted years after his presumed death. He states unequivocally on the title pages that he is writing “in stil moderno.” This means, among other things, frequent changes of tempo and character which he often indicates with words like “alegra” and “adagio,” a new development in notation at that time. Nevertheless, vestiges of the older Venetian school are still to be found. Sonata 15 begins rather like a madrigal, with the parts moving together in a speech-like rhythm. The piece mostly consists of four canzona-like sections, each starting in a different voice, with a contrasting middle section in a lilting triple metre.

Published in 1673, La Cetra by Giovanni Legrenzi falls right at the midpoint of the baroque era. He was a highly regarded composer in Venice at the time. In the one sonata for the unusual number of four violins, he demonstrates his mastery of writing with many motives. At the outset the violins each enter systematically in turn with the first one, then toss around three others more freely, then the pattern repeats in a different order. The contrasting middle movements venture to other keys, then the home key is found again in the dance-like finale.

Arcangello Corelli was the dominant violinist and instrumental composer in Rome for decades, serving its many churches and wealthy families. He was revered for the refinement both of his playing and compositions, and also for his skill as an orchestral leader. While considered the leading exponent of the concerto grosso, his works in that form only appeared in print posthumously. The concertos are designed so that, while they can be played by a trio group alone (concertino), they realize their full potential with the addition of larger group of strings (ripieno) playing in dialogue to create large dynamic contrasts. Accounts of Corelli’s own performances show that the ripienocould even include wind instruments, as we are doing in the final concerto of the concert.

Matthew Locke was England’s first great composer for the theatres once they reopened after the Restoration. His music for a revival and reworking of Shakespeare’s The Tempest is particularly significant for the Curtain Tune that begins the action of play. It vividly evokes the storm itself, with instructions to begin softly and very gradually swell the sound as the pace of the music accelerates until an outburst of fast notes marked, unambiguously, “Violent.”

The remaining music is mostly from the “First and Second Music” that precede the actual play and are not related to the plot as such. The title “Lilk” does not appear elsewhere in music to my knowledge, but resembles the maritime hornpipe.

L’Estro Armonico, Antonio Vivaldi’s Opus 3, was his first great success and one of the most reprinted publications of the eighteenth century. The eighth concerto is among the most popular, partly due to a transcription for organ by Bach. The interplay of the parts is more important here than the large contrasts of Corelli. Particularly striking is the juxtaposition of a cantabile (singing) melody and virtuoso passagework in the last movement. ■

Image captions

1. The interior of San Marco in Venice, with some of numerous galleries from which musicians performed, often in dialogue.

2. Title page of Castello's 1629 publication of sonatas "in stil moderno."

3. Dulcian