As part of our Bohemian Rhapsody: Haydn & Benda program next week, Tafelmusik’s own Keiran Campbell takes centre stage as soloist in Haydn’s show-stopping Cello Concerto in C Major.

We caught up with Keiran as he prepares for his upcoming solo to chat about cellos old and new, Haydn’s sense of humour, and what makes this concerto so special.

How would you describe the cello’s first entry in the Haydn concerto?

The cello enters in the very first solo like a rambunctious child, jumping gleefully while trying—and failing—to feign a noble composure, stomping all over the place with almost comical chords. Lyrical motifs develop, only to be immediately interrupted by bubbling flourishes of scampering notes.

So Haydn’s reputation for having a good sense of humour is well deserved?

Absolutely! The way Haydn writes the solo part in this concerto almost borders on the absurd, as he constantly contrasts a rather hyperactive joy with moments of serenity. In his writing you can find so many humorous moments, the most notable being in his Symphony No. 60, nicknamed ‘Il Distratto,’ where the rambunctious finale stops abruptly to allow the violins to “tune”: Haydn writes a series of sustained fifths for the violins to play—with two bars of rest on either end— before the music bursts back to life.

Tickets on sale now for Bohemian Rhapsody: Haydn & Benda, featuring Keiran Campbell playing on a cello from 1707

When did you first play the Haydn concerto, and where else have you performed it?

I’m not entirely sure where I first performed it, but I’m guessing it was for one of those local youth concerto competitions (I clearly didn’t win that year). I do remember my father, who is a wonderful clarinetist, coaching me a lot on the Haydn Concerto as a child. Although I’ve not actually told him this, there are a few phrases where I remember very clearly the images he described as he tried to coax the music out of me. For example, there is one phrase in the first movement that soars in a really lovely way, and he compared it to a flower blooming.

I think the first time I played it professionally was with my friend William Kelley. Will had started an orchestra in our home state of North Carolina, and we were both in school at Juilliard at the time. It was a blast to perform together, and Will has since gone on to have a fantastic conducting career. He is now the Kapellmeister at Theater Bremen.

I’ve played this piece many times since and in some interesting places, including quite a few 7am coaching sessions on top of the ruins of a castle in Bavaria, where my dear teacher Leonid Zilper, former solo cellist of the Bolshoi Ballet, informed me that the 10C temperature would prepare my hands for any concert situation.

Tell us about the cello you’ll be playing in these concerts. Is it especially suited to this repertoire?

This cello is a very special instrument, built by Giovanni Grancino in 1707 in Milan, right at the end of his life. This cello marks an interesting transition point when most luthiers were beginning to abandon the larger model cellos in favour of smaller, easier-to-navigate instruments. Of course, the larger bassi weren’t suddenly cast aside, and they were used side by side with the smaller celli until the turn of the 19th century, when most of the large instruments were cut down in size to conform to the smaller instruments, which were becoming more or less the standard. During this process of standardization, a larger cello might have sections of the body reduced to make it smaller, and the necks were usually replaced as they might have been too short or too long.

Somehow this cello escaped all of those changes. My guess is that it was perhaps hidden away for quite some time, unplayed for a number of years. It retains its original dimensions, original neck, and even the original bass bar (which serves both acoustical and structural purposes). My favorite detail is the “processional hole” on the back of the instrument. Early 18th-century musicians would bore a hole in order to attach a strap, so they could play standing up in parades, church services, or at parties. Interestingly, most of the great 17th and 18th-century Italian cellos have this feature—not even Strads were safe in those days!

This Grancino has been on a generous loan to me thanks to Christophe Landon Rare Violins in New York. I’ve had the instrument for about half a year, and although I will sadly be returning it after this project, I am so grateful for the opportunity I’ve had to learn from this magnificent cello!

According to deep Internet lore, as a child you used to make paper models of instruments. Now you make real instruments using wood. Can you tell us more about that?

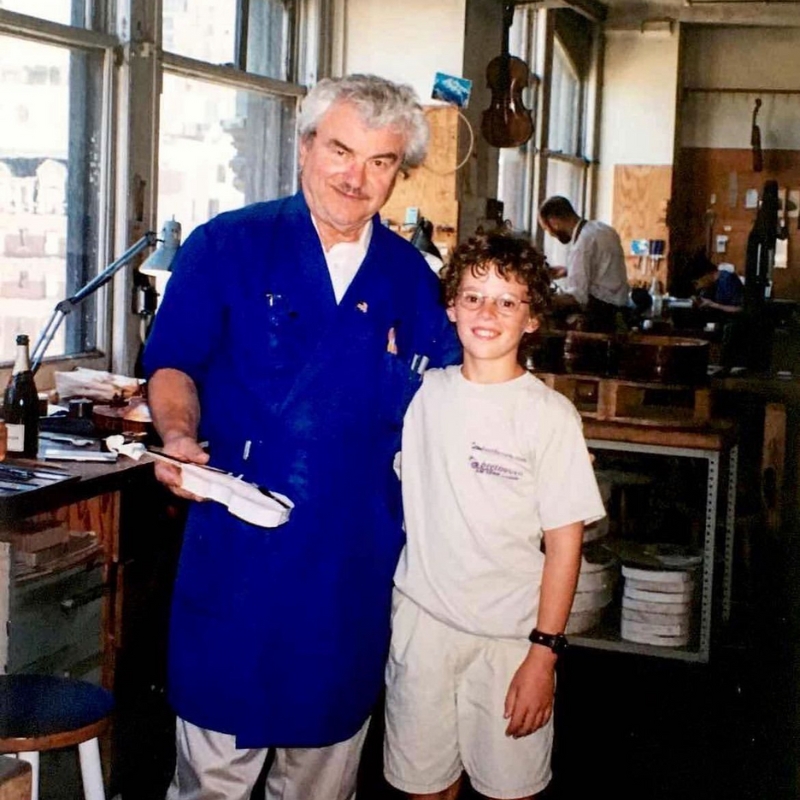

Since I was a child, I’ve always had a drive to create, both through making music, and making physical objects. Soon after starting the cello at age eight, I became fascinated with stringed instruments and how they were made. My family often took trips up to New York to visit relatives, and on one of these trips I paid a visit to Rene Morel, who at that time was essentially the god of violin restoration. Itzhak Perlman, Issac Stern, Yo-Yo Ma, and Pablo Casals all trusted him with their precious instruments. I presented him with a small violin I had made out of paper, and he promptly took me into the workshop to give me a tour. At one point during the visit, he took an old violin down from the wall and handed it to me, saying “here, this is a Stradivari violin, take a look.” There was absolutely no turning back after that!

Eventually, I tried to make a few instruments from cheap wood and woefully dull tools, but it wasn’t until I met Timothy Johnson (the maker of my baroque cello) that I began to really study the craft. Over the course of the pandemic, I made several week-long trips to his workshop in Connecticut, where we worked together on my first “real” violin. I really treasure the time I spent there, making instruments by day, and sleeping in the loft of the barn at night! Tim and I have become good friends, and I often return to his workshop to continue learning, and also to help with some more labour-intensive projects, like cello building!

I would be remiss if I did not also mention Chris Ruffo, a fantastic Canadian violin maker. He has been incredibly generous to me and Tafelmusik. The other year, he made and donated a beautiful Nicola Amati-patterned violin to the Jeanne Lamon Instrument Bank. More recently, he very kindly gave me some tools to help get my workshop up and running. The violin-making world is a wonderful place!

Keiran Campbell has performed with ensembles including The English Concert, NYBI, Philharmonia Baroque, The Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra, Four Nations Ensemble, and Les Violons du Roy. He is also on faculty at the recently formed, UC Berkeley-based, Chamber Music Collective, which focuses primarily on post-1750 performance practice.

Thank You to our Generous Donor

Keiran Campbell extends his thanks to Christophe Landon for the generous loan of a cello made by Giovanni Battista Grancino (Milan, 1707) for this week’s performances of the Haydn Cello Concerto.